The Byzantines and the government of Sardinia

The word “Byzantine” comes from the ancient name of the Greek town Byzantion, founded in the VII century B.C. on the site of the present day Istanbul in Turkey, on the Bosphorus (fig. 1).

In 324 Constantine decided to build a new city on the older one and it became the empire's new capital in 330 A.D. (fig. 2) with the name Nea Roma (New Rome), or, alternatively, Constantinople (City of Constantine).

After the Western empire was separated from the Eastern one in 395, the latter extended and lasted until 1453, when it was conquered by the Ottomans.

During the reign of Justinian (527-565 - fig. 3), the Byzantines managed to steal Sardinia from the Vandals in 534.

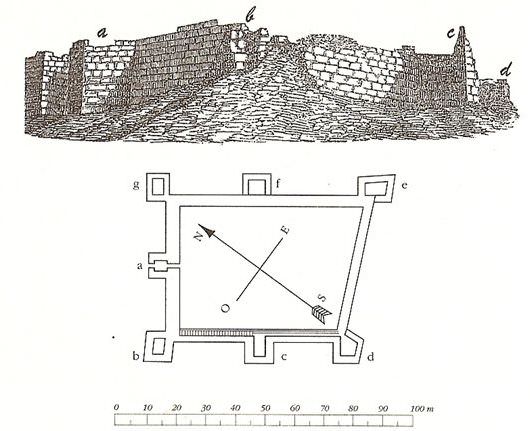

As of that date, the military command of the island was held by a dux Sardiniae with its headquarters «in the mountains where the Barbaricini were thought to live», place assumed to be Fordongianus. It exercised military functions, handled organisation and the defence efficiency of fortresses (castra) spread over the area, especially in the most exposed centres and the most important ones like Karales (Cagliari), Sulci (Sant’Antioco - fig. 4), Tharros, Forum Traiani (Fordongianus), Olbia, Turris Libisonis (Porto Torres).

In 687 Giustiniano II ordered, perhaps for safety reasons, that the dux be transferred to Cagliari where the praeses, official holding administrative functions, was already based. At times of particular danger, the two figures became a single official - called iudex provincae or archon - charged with handling threats. Progressively, that figure increased his autonomy until the Districts were slowly created and the Byzantine government came to an end in Sardinia.

Bibliografia

- A. BOSCOLO, La Sardegna bizantina e alto-giudicale, Sassari 1978, pp. 27-32.

- S. COSENTINO, Potere e istituzioni nella Sardegna bizantina, in P. CORRIAS, S.

- COSENTINO (a cura di), Ai confini dell’impero: storia, arte e archeologia della Sardegna bizantina, Cagliari 2002, pp. 1-13.

- A. F. LA MARMORA, Itinerario dell’isola di Sardegna, 1 = Bibliotheca Sarda, 14, Nuoro 1997, p. 258.

- R. MARTORELLI, La diffusione del cristianesimo in Sardegna in epoca vandala, in R. M. BONACASA CARRA, E. VITALE (a cura di), La cristianizzazione in Italia fra Tardoantico e Altomedioevo. Atti del IX Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Cristiana (Agrigento, 20-25 novembre 2004), I-II, Palermo 2007, pp. 1419-1448.

- G. MELONI, L’origine dei giudicati, in M. BRIGAGLIA, A. MASTINO, G. G. ORTU (a cura di), Storia della Sardegna 2. Dal Tardo Impero romano al 1350, Roma 2002, pp. 1-32.

- F. PINNA, Le testimonianze archeologiche relative ai rapporti tra gli Arabi e la Sardegna nel Medioevo, in Rivista dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea, IV, 2010, pp. 11-37.

- P. G. SPANU, La Sardegna bizantina tra VI e VII secolo, Oristano 1998, pp. 16, 65.

- W. TREADGOLD, Storia di Bisanzio, Bologna 2009, pp. 32-34, 80-81.

VR

VR