Refrigerium rite

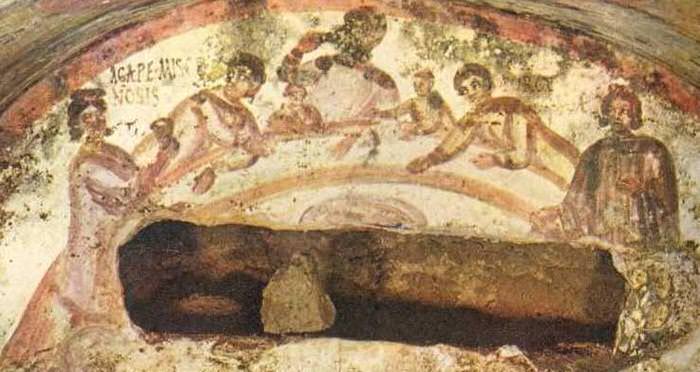

The term refrigerium comes from the verb cool down or refresh in the meaning of relief due to a meal, but also peace and rest. The funeral meal gets its name from that, certified from the IV to VII century A.D. and identified as a ritual practised in pagan religions, then included in the Christian one in the first centuries (see fig. 1).

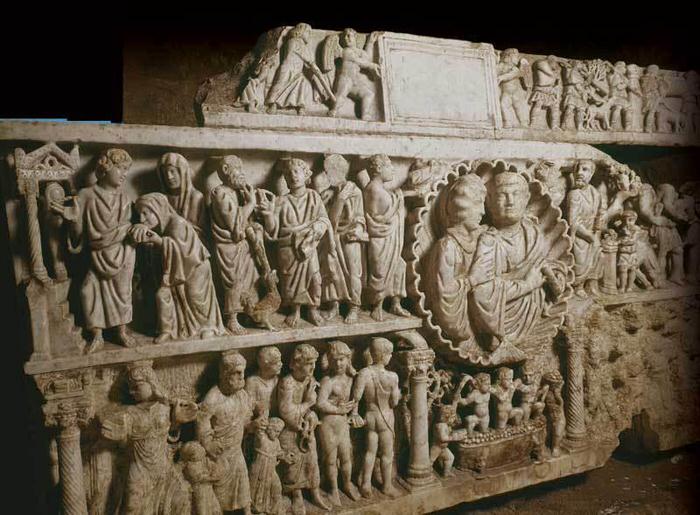

The first banquet celebrated in honour of the deceased was held straight after burial and then on the third, seventh and ninth day, then on the thirtieth or fortieth and lastly every year on the day of his/her death (dies natalis). Relatives and friends of the deceased took part and it took place next to or on the tomb itself, as the purpose of the meeting was to remember the dead person who, in common belief, was present at the meal. Last of all, the word refrigerium indicated the augury of eternal blessing for the soul of the deceased and enjoyment for his/her body, expressed in the epigraphs and funerary paintings (figs. 2-4).

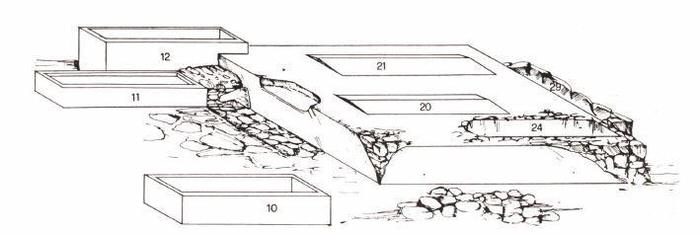

Besides the banquet for the living, it was customary to introduce foods like milk, honey and wine into the burial together with perfumed unguents, which were the libation: holes were made in the burial to insert fictile or metal libation pipes, which the substances dripped from (fig. 3). In the Cornus cemetery, one of this pipes was found in the tomb of Limenius.

The religious authorities tried to block the ritual, because of how things degenerated at the end of the meals as they turned into real orgies.

Banquets were proven in catacombs and open-air cemetery areas through structures used for the rite, such as pulpits, klinai and brick tombs protected in the rocks: the pulpits were the symbol of the presence of the deceased at the refrigerium in his/her honour. The klinai are seats or beds cut out of the slabs covering some sarcophagi, used by banqueters.

The tables were used for a group of burials. They were of various shapes - circular, semicircular, square, rectangular - at times with an inscription (fig. 4) or a decoration in relief and at times had small cavities for offerings. They proved that the ritual meals took place. In fact, the remains of meals, fictile and glass recipients in fragments and coal from fires lit for the occasion were found near them.

In Sardinia, the tables have been found in various places, for example Sant’Imbenia (Alghero), Santa Filitica (Sorso), Su Gutturu necropolis (Olbia), Porto Torres, S. Saturnino (Cagliari), San Cromazio (Villa Speciosa) and Columbaris (Cuglieri - figs. 5-6).

Bibliografia

- F. BISCONTI, V. FIOCCHI NICOLAI (a cura di), Riti e corredi funerari, in L. PANI ERMINI (a cura di), Christiana loca. Lo spazio cristiano nella Roma del primo millennio, II, Roma 2000, pp. 61-96.

- A. CORDA, Le iscrizioni cristiane della Sardegna anteriori al VII secolo, Città del Vaticano 1999, p. 62.

- A. CORDA, Breve introduzione allo studio delle antichità cristiane della Sardegna, Ortacesus 2007, p. 55.

- P.-A. FÉVRIER, À propos du repas funéraire: culte et sociabilité, in Christo Deo, pax et concordia sit convivio nostro, in Cahiers archéologiques. Fin de l’antiquité et Moyen âge, XXVI, 1977, pp. 29-45.

- J.-A. FÉVRIER, Le culte des morts dans le communautés chrétiennes durant le IIIe siècle, in Atti del IX Congresso Internazionale di Archeologia Cristiana (Roma, 21-27 settembre 1975), Città del Vaticano 1978, pp. 221-302.

- V. FIOCCHI NICOLAI, Origine e sviluppo delle catacombe romane, in V. FIOCCHI NICOLAI, F. BISCONTI, D. MAZZOLENI, Le catacombe cristiane di Roma. Origini, sviluppo, apparati decorativi, documentazione epigrafica, Regensburg 2002, pp. 9-69.

- A. M. GIUNTELLA, Sepoltura e rito: consuetudini e innovazioni, in AA. VV., Le sepolture in Sardegna dal IV al VII secolo. IV Convegno sull'archeologia tardoromana e medievale (Cuglieri 27-28 giugno 1987) = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 8, Oristano 1990, pp. 215-230.

- A. M. GIUNTELLA, Note su alcuni aspetti della ritualità funeraria nell’alto medioevo. Consuetudini e innovazioni, in G. P. BROGIOLO, G. WATAGHIN (a cura di), Sepolture tra IV e VIII secolo. 7° Seminario sul tardo antico e l’alto medioevo in Italia centro settentrionale (Gardone Riviera, 24-26 ottobre 1996) = Documenti di archeologia, 6, Mantova 1998, pp. 66-67.

- A. M. GIUNTELLA, Cornus I.1. L'area cimiteriale orientale = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 13. 1, Oristano 1999, p.52-53, 57.

- A. M. GIUNTELLA (a cura di), Cornus I. 2. L'area cimiteriale orientale. I materiali = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale, 13. 2, Oristano 2000, p. 14.

- A. M. GIUNTELLA, G. BORGHETTI, D. STIAFFFINI, Mensae e riti funerari in Sardegna: la testimonianza di Cornus = Meditarraneo Tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 1, Taranto 1985, pp. 29, 31, 34, 39, 44, 57, 59, 85.

- B. HAMMAN s.v. Refrigerium, in Dizionario Patristico e di Antichità Cristiane, Casale Monferrato 1984 coll. 2977-2978.

- E. JASTRZEBOWSKA, Untersuchen zum christlichen Totenmahl aufgrund der Monumente des 3. und 4. Jahrunderts unter der Basilika des Hl. Sebastien in Rom, in Europäische Hochschulschriften Archäeologie, XXXVIII, Frankfurt a. M., 1981.

- E. JOSI, Il cimitero di Panfilo, in Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana, I, 1924, pp.15-119.

- T. KLAUSER, Die Cathedra in Totenkult der heidrischen und christlichin Antike, in Liturgiegeschichtliche Quellen und Forshungen, 7, Münster/W 1927.

- D. LISSIA, Alghero loc. S. Imbenia. Insediamento e necropoli di età tardo-antica e altomedievale, in AA. VV., Il suburbio delle città in Sardegna: persistenze e trasformazioni. Atti del III Convegno di studio sull’archeologia tardoromana e altomedievale in Sardegna (Cuglieri, 28-29 giugno 1986) = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 7, Taranto 1989, pp. 29-38.

- D. LISSIA, D. ROVINA, Sepolture tardo romane e altomedievali nella Sardegna nord-occidentale e centrale, in AA. VV., Le sepolture in Sardegna dal IV al VII secolo. IV Convegno sull'archeologia tardoromana e medievale (Cuglieri 27-28 giugno 1987) = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 8, Oristano 1990, pp. 75-100.

- G. MANCA DI MORES, Sepolture tardo romane e altomedievali nella Sardegna nord-occidentale, in AA. VV., Le sepolture in Sardegna dal IV al VII secolo. IV Convegno sull'archeologia tardoromana e medievale (Cuglieri 27-28 giugno 1987) = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 8, Oristano 1990, pp. 101-104.

- M. MARINONE, I riti funerari, in L. PANI ERMINI (a cura di), Christiana Loca. Lo spazio cristiano nella Roma del primo millennio, I, Roma 2000, pp. 71-80.

- L. PANI ERMINI, La Sardegna e l’Africa nel periodo vandalico, in A. MASTINO (a cura di), L'Africa romana. Atti del II Convegno di studio (Sassari, 14-16 dicembre 1984), Sassari 1985, pp. 105-122.

- G. PIANU, Sulla “Iglesia de San Gromar”, in P. G. SPANU (a cura di), con la collaborazione di M. C. OPPO e A. BONINU, Insulae Christi. Il cristianesimo primitivo in Sardegna, Corsica e Baleari = Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche 16, Oristano 2002, pp. 443- 450.

- D. ROVINA, Santa Filitica a Sorso, dalla villa romana al villaggio bizantino, Viterbo 2003.

- A. TEATINI, “Sepulti in refrigerio”. Nuove testimonianze paleocristiane da San Cromazio, in Dal mondo antico all'età contemporanea: studi in onore di Manlio Brigaglia offerti dal Dipartimento di storia dell'Università di Sassari = Collana del Dipartimento di Storia dell’Università degli studi di Sassari, Nuova serie 7, Roma, 2001, pp. 151-169.

- A. TEATINI, Archeologia cristiana: Villaspeciosa ancora scoperte a San Cromazio, in Almanacco gallurese, 10, (2002-2003), 2003, pp. 65-70.

- P. TESTINI, Archeologia Cristiana, Bari 1980, p. 144, 147-148.

VR

VR