Siege techniques

During the Middle Ages the birth of castles and fortified villages meant that military operations often evolved into siege warfare. In order to storm fortifications, the ancient art of poliorcetics was employed.

The builders of castles paid special attention to the strength of the walls and towers and tried to provide this as much as possible to the entrance, which was the weakest point of the structure.

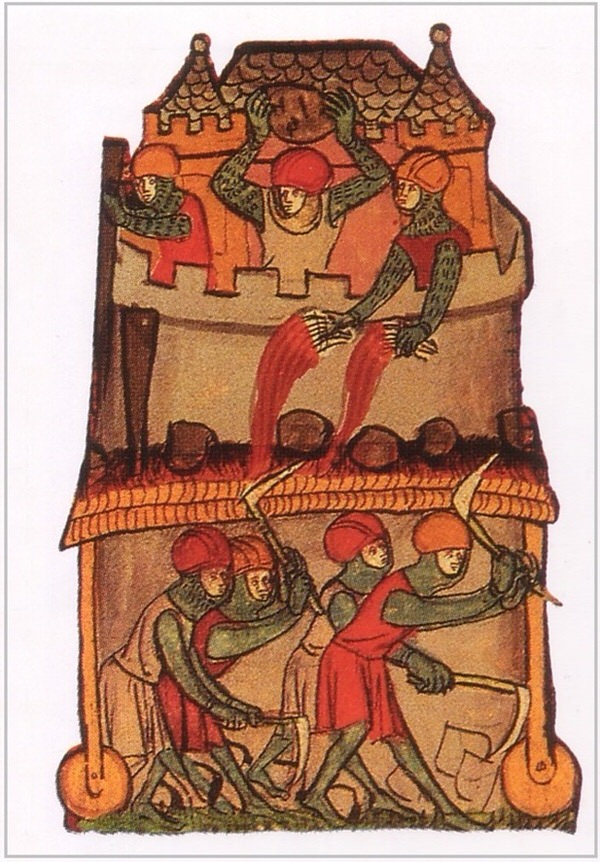

Ditches were dug around the building and its access was defended by a drawbridge, a portcullis and actual doors. The walkways along the walls were protected by battlements, so that the guards could shelter during the fighting. Subsequently, the battlements were also given a protruding parapet which rested on shelves and was provided with trap doors through which stones, boiling water and quicklime were thrown onto the enemy. Many fortresses had towers which jutted considerably compared with the curtain walls, in order to effectively attack enemies trying to climb the walls.

The main siege technique was to surround the fortress preventing supplies of food and waiting for the enemy to surrender by starvation. However, many castles were organised to resist isolation for several years.

The building therefore needed to be attacked by trying to overcome its "security systems" through targeted actions; for example, using a particularly effective technique, such as that of "mines", which consisted in digging a tunnel in order to reach under the curtain walls of the building, so as to cause their collapse under their own weight (fig. 1).

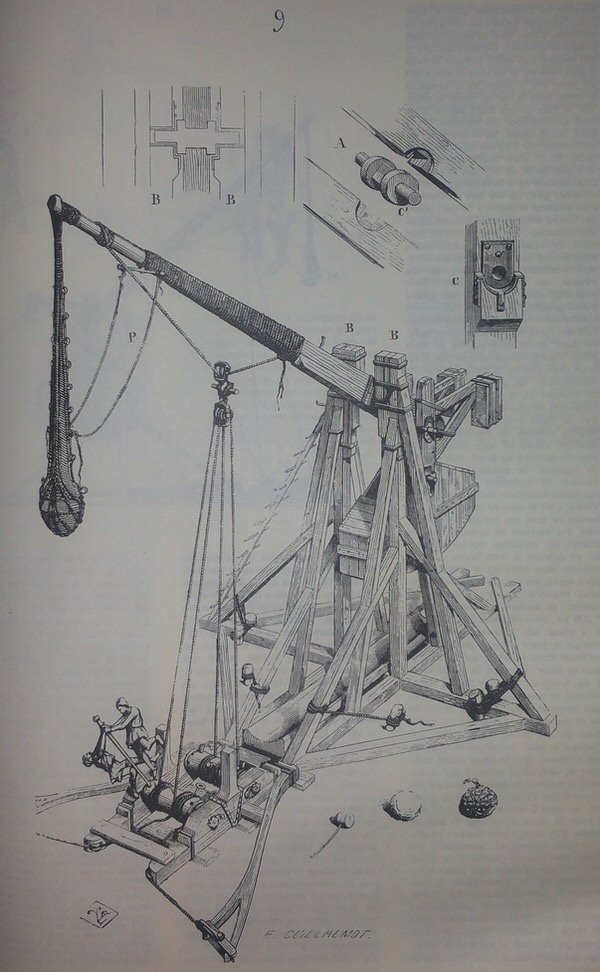

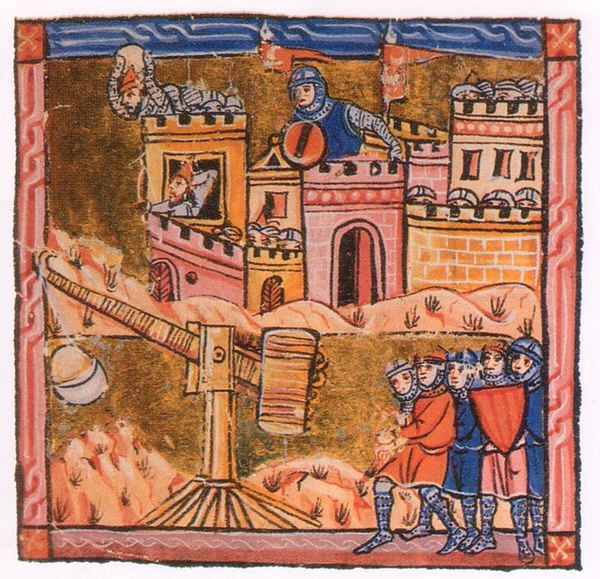

War machines were also very useful for attacking fortified walls. Among these, the trebuchet was one of the most powerful, since it could launch its projectiles up to a distance of 300 metres and to a considerable height (figs. 2-3). Ammunition usually consisted of stones and boulders, although sometimes human heads or, in the hope of causing epidemics, the carcasses of infected animals were thrown.

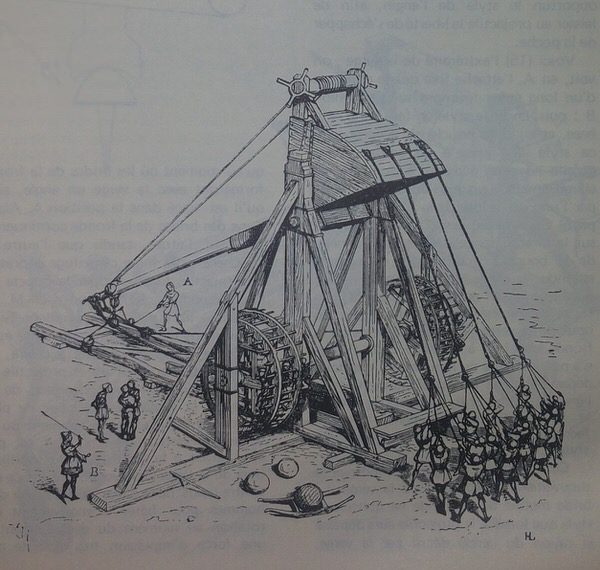

The mangonel was similar to the trebuchet, but smaller and more powerful; it threw projectiles with great violence and with a linear trajectory, in order to achieve maximum impact against the walls (fig. 4).

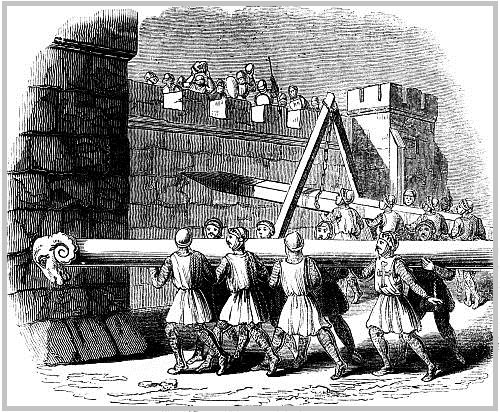

The ram consisted of a sturdy wooden trunk with the tip reinforced with an iron ram head, in order to increase its strength. It was horizontally attached to a support structure and after placing it close to the walls or to the front door that it was intended to force, it was swung until it hit these hard (fig. 5).

Climbing the fortified walls with simple ladders was a complicated and difficult undertaking, which exposed the besiegers to deadly blows from the castle defenders. It was therefore necessary to build moving wooden towers, as high as the walls to be attacked. After placing the tower against the walls, the soldiers reached the top thanks to internal stairs and with the help of a drawbridge, could easily step onto the walls.

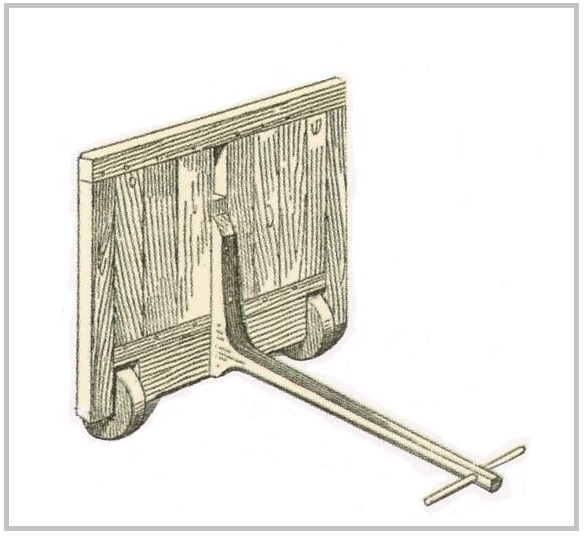

In order to approach the castle without running the risk of being struck by arrows and darts thrown by the defenders of the castle, and perhaps reach the base of the walls and try to remove its stones, the assailants used small movable wooden palisades, equipped with slits, called "mantelets" (fig. 6).

Bibliografia

- E.E. VIOLLET LE DUC, Encyclopédie Médiévale, tome I, Tours 2002.

- C. GRAVETT, I castelli medievali, Novara 1999.

- G. OSTUNI, s.v. Poliorcetica, in Enciclopedia dell' Arte Medievale, IX, 1998, pp. 600-606.

- U. BADALUCCHI, s.v. trabocco, in Enciclopedia Italiana (1937) http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/trabocco_%28Enciclopedia_Italiana%29/

- M. BORGATTI, s.v. mangano, in Enciclopedia Italiana (1934)

http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/mangano_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/ - M. BORGATTI, s.v. ariete, in Enciclopedia Italiana (1929)

http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ariete_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/

VR

VR