Carnelian scarab

Several scarab-seals have been found in the necropolis of Sant’Antioco, including a bright red one in Carnelian (or cornelian) from tomb 6 PGM, consisting of a single chamber, carefully painted and characterised by two schematic bethels sculpted on the back wall, dating from the fifth century B.C.

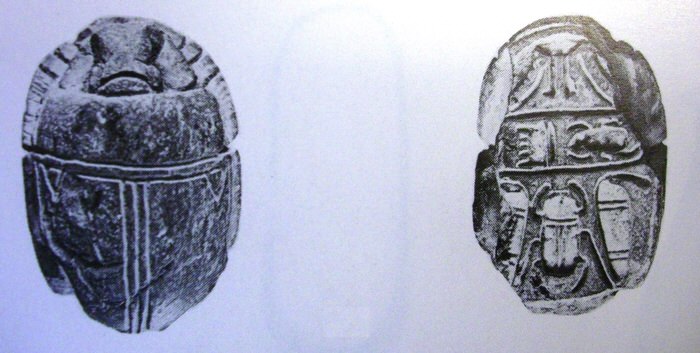

The small scarab (1.2 x 1.1 x 0.9 cm), has a gold mount formed by a ring (1.7 x 1.5 cm) with spiral ends and a hook obtained by torsion (figs. 1-3).

The back has the shape of the insect: a vertical cut line creates the small gap between the elytra, i.e. the plates which in the insect hide and protect its wings; another line, almost a "V", instead delimits the prothorax, i.e. the part between the head and the thorax to which the elytra are connected (fig. 4). The head appears much worn and the legs in relief can be seen on the sides (figs. 1-2).

A Greek-style human male is engraved on its oval base within a string frame, naked, running towards the right, with a cap headdress (maybe a helmet) from which curls escape on the front and on the neck. The character has his left arm bent behind the body and with his hand he grips a sort of branch which bends over him, forming an arc that follows the contour of the oval and ends with a fruit or a flower towards which he extends his arm with open right hand, while trying to pluck it (fig. 3). The iconography is, as mentioned, Greek-style, but Punic scarabs also have many Egyptian, Etruscan and Eastern-style images and scenes, in addition to those of mixed type, which blend design elements from different cultures.

The technique used is that of freehand carving and engraving and of the round tip drill, which renders the muscles of the body and the details of the face, according to the procedure of the so-called mixed technique. The scarab has a classic longitudinal drilling, which allows inserting the setting. The object is made of hard semiprecious stone and gold, finely worked, and is certainly a luxury item which must have belonged to a wealthy person.

The carnelian stone is the second most common stone in Punic engraved gems, and in particular in Sardinia, after the green jasper which is the preferred one for creating scarab-seals (fig. 6). Other semi-precious stones used are the agate, rock crystal, chalcedony. However several specimens, mainly belonging to the Phoenician period (VII-VI century B.C-) are in paste or steatite.

Both the green of the jasper and the red of the carnelian were linked to rebirth, and were often used to create other amulets. The scarab was indeed an amulet, and therefore maintained a certain protective value, accompanying the deceased in the afterlife, but it was also a personal seal, which could represent a sign of recognition of some officer, a priest or a wealthy person who covered some important role. It is also believed that they could represent a kind of "coat of arms" of the family, without excluding a religious significance, linked to mystery cults. The practical use of the scarab as a seal is supported by the discovery of numerous cretulae (seals) in several sites, including Selinunte and Carthage itself, while in Sardinia, at Cuccureddus Villasimius, only 5 have unfortunately been found up to now (fig. 7).

Two soapstone scarabs were also found in Sulky, both believed to be imported and datable to an archaic period between the seventh and early sixth centuries B.C.: the first one perhaps from Egypt (fig. 8) and the second from Phoenicia (fig. 9) taking into consideration the inscription in Phoenician, a characteristic that is difficult to find in West Punic scarabs.

Bibliografia

- E. ACQUARO, A. LAMIA, Archivi e sigilli di Cartagine, Lugano 2010.

- J. BOARDMAN, Classical Phoenician Scarabs, Oxford 2003.

- R. DE SIMONE, Tradizioni figurative greche nella ‘Selinunte punica’: le cretule del tempio C in M.CONGIU, C. MICCICHÈ, S. MODEO, L. SANTAGATI (a cura di),Greci e Punici in Sicilia tra V e IV secolo a.C. Atti del IV Convegno di Studi (Caltanissetta 6-7 ottobre 2007), Caltanissetta 2008, 31–45.

- G. DEVOTO, A. MOLAYEM, Archeogemmologia. Pietre antiche, glittica magia e litoterapia, Roma 1990.

- S. MOSCATI, Le officine di Sulcis, Roma 1988.

- C. OLIANAS, Scarabei in pietra dura della Sardegna punica (fine VI-III sec. a.C.) nel Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari. Catalogazione e analisi iconografiche-stilistiche e tipologiche, Tesi di dottorato, Università degli Studi di Padova, a.a. 2011-2012.

- T. Redissi, Etude des empreintes de sceaux de Carthage in F. Rakob (a cura di), Karthago III. Die deutschen Ausgrabungen in Karthago, Mainz am Rhein 1999, pp. 4-92.

- A. SECHI, Athyrmata fenicio-punici: la documentazione di Sulcis (CA), tesi di laurea, Università degli Studi di Pisa, a.a. 2005-2006.

- J. VERCOUTTER, Les objects égyptiens et ègyptisants du mobilier funéraire carthaginois, Paris 1945.

VR

VR