Necropolis of Is Pirixeddus

- Punic Age - Roman Age - Late Ancient Age, end VI century B.C. - VII century A.D.

The ancient Punic inhabitants of Sulky, the current town of Sant'Antioco, used to bury their dead in the cemetery, which at the time was located outside the town, and whose graves were dug on a rocky hill, as was typical for the Punic people and was also the case in Carthage and Cagliari (Tuvixeddu).

What we know today, which is still visible and at least partially open, is what remains of the Punic necropolis, which grew between the end of the VI - V centuries and about the third century B.C. (fig. 1), while the Phoenician necropolis was identified thanks to sporadic findings, near the present Via Perret, in the lower part of the town, towards the sea, and dates back to the seventh century B.C.

The Punic necropolis was later reused by the Romans both during the Republican age (between the second and first centuries B.C.) and then in the imperial one (at least for the first century A.D.) (fig. 2).

Later, from the fourth and fifth centuries AD, the necropolis was used by early Christians as a catacomb, joining different burial chambers through openings in the common walls between the various spaces, thereby creating new burial areas either through rectangular pits dug in the floor, or by excavating the wall in order to create a recess in which to dig a sarcophagus in the lower part while the upper part was arched (arcosolium tomb); sometimes these tombs are decorated with paintings.

The two main sections of the catacombs are located under the parish church:

1) Catacombs of Sant'Antioco;

2) Catacombs of Santa Rosa, also under the church, very small, consisting of only two environments (fig. 3).

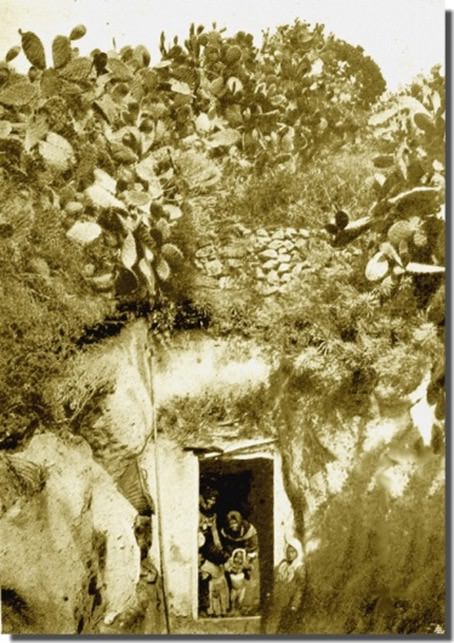

Another complex which was reused in the modern era and up to recently (end of the 70’s of the twentieth century) consists of the houses in the underground village. Some graves were also reused as cellars and storage rooms and still perform that function (figs. 4-5).

The most famous part of the necropolis is located on the eastern and north-eastern slopes of the hill now occupied by the Savoy stronghold of Su Pisu (fig. 6), which shows visitors the most common type of tomb within the funerary area, the underground chamber tomb, with an access corridor called dromos (fig. 7).

This corridor leads to the burial chamber, through a landing which served to position the deceased for his entry into the chamber, which often occurred on a wooden stretcher, while the sometimes carved and tastefully decorated sarcophagus could be assembled inside the room. The entrance to the burial chamber was located at the end of the stairs and in front of the landing (fig. 8).

It could have consisted of a large room divided by a partition whose front could be decorated both by very simple carved architectural elements (a projecting band representing a capital for example), and by real high-reliefs: this is the case of the two tombs, one discovered in 1968, the other in 2002, in which the partition (in the first one) and the central pillar (in the second one) were decorated with a life-size relief, representing an Egyptian-style figure, i.e. dressed and presented as an Egyptian (fig. 9).

He is in fact striding, his right arm to his chest and his left along the body, and is depicted with a beard and wearing a short skirt and klaft, the typical kerchief which is often found in the iconography of the Egyptian people, first of all the pharaohs.

The rooms could therefore hold one or more deceased over time and when the density of the underground graves left no more room for new burials, new rooms were obtained by digging at different levels from those which had previously been excavated. In addition to the underground graves with a large room divided by a partition, we can also find those with a single burial chamber, which represent the older type (fig. 10).

The tombs have no precise orientation characterising them, but appear to have been dug with no particular layout (fig. 11).

The deceased was laid, wrapped in a shroud or a tunic, inside the burial chamber on a wooden stretcher or in a sarcophagus, with his accompanying goods and all the items relating to the funeral ritual, such as terracotta pottery, terracotta or coloured glass ointment-holders and his personal items, such as necklace amulets and pearls made of glass paste, scarabs, jewellery (rings, necklaces, earrings), razors and various objects which tell us something about the deceased, whether man, woman or child, and in some cases may reveal what job he had when alive (fig. 12).

Bibliografia

- M.G. AMADASI GUZZO, C. BONNET, S.M. CECCHINI, P. XELLA (a cura di), Dizionario della civiltà fenicia, Roma 1992

- F. BARRECA, L’attività della Soprintendenza Archeologica per le province di Cagliari e Oristano (1970-1986) = QuadCa 1986, pp. 3-18.

- P. BARTOLONI, Sulcis, Roma 1989.

- P. BARTOLONI, Testimonianze dalla necropoli fenicia di Sulky = Sardinia Corsica et Baleares Antiquae 7, 2009,

pp.71-80. - P. BARTOLONI, 1987, La tomba 2AR della necropoli di Sulcis = RSF vol. XV, 1, Roma, pp. 57-73.

- P. BARTOLONI, Sulcis, 1989 Roma.

- P. BARTOLONI, In margine a una tomba punica di Sulcis = QuadCa 1993, Cagliari, pp. 93-96.

- P. BARTOLONI, Il museo archeologico comunale “F. Barreca” di Sant’Antioco, Sassari 2007

- P. BARTOLONI, I Fenici e i Cartaginesi in Sardegna, Sassari 2009

- P. BERNARDINI, I leoni di Sulci in Sardò 4, Sassari 1988.

- P. BERNARDINI, 1999, Sistemazione dei feretri e dei corredi nelle tombe puniche: tre esempi da Sulcis = RSF vol. XXVII, 2, Roma, pp. 133-146.

- P. BERNARDINI, Recenti scoperte nella necropoli punica di Sulcis = RSF, vol. XXXIII, Roma 2005, pp. 63-80.

- P. BERNARDINI, Recenti ricerche nella necropoli punica di Sulky, in S. ANGIOLILLO, M. GIUMAN, A. PASOLINI, Ricerca e confronti 2006. Giornate di studio di archeologia e storia dell’arte, Cagliari 2007

- P. BERNARDINI. Aspetti dell’artigianato funerario punico di Sulky. Nuove evidenze, in M. MILANESE, P. RUGGERI, C. VISMARA (a cura di), Atti del XVIII Convegno Africa Romana (Olbia, 11-14 dicembre 2008), Roma 2010, pp. 1257-1270.

- M. GUIRGUIS, Storia degli studi e degli scavi a Sulky e Monte Sirai = RSF XXXIII, 1-2, Roma 2005.

- S. MUSCUSO, La necropoli punica di Sulky, in M. GUIRGUIS, E. POMPIANU, A. UNALI (a cura di), Quaderni di Archeologia Sulcitana 1. Summer School di Archeologia Fenicio Punica (Atti 2011), Sassari 2012.

- S. PUGLISI, Scavo di tombe ipogeiche puniche (Sant’Antioco) = NSc (1942), pp. 106-115.

- G. PESCE, Un dipinto romano in una tomba dell’antica Sulcis = BA, 2-3, 1962, pp. 264-268.

- G. SPANO, Descrizione dell’antica città di Sulcis =

- A. TARAMELLI, S.Antioco - Scavi e scoperte di antichità puniche e romane nell’area dell’antica Sulcis = NBAS, 1908, pp. 145-162.

- C. TRONCHETTI, Sant’Antioco (Cagliari) - Scavo nelle necropoli puniche = NBAS 1985, pp. 285-286.

- C. TRONCHETTI, S. Antioco, 1989 Sassari.

- C. TRONCHETTI, Nuove acquisizioni su Sulci punica : AA. VV., Incontro « I Fenici », Cagliari 1990, pp. 63-68.

- C. TRONCHETTI, Le problematiche del territorio del Sulcis in età romana in V. SANTONI (a cura di), Carbonia e il Sulcis. Archeologia e territorio, Oristano 1995.

- C. TRONCHETTI, 1997, La tomba 12 (A.R.) della necropoli punica di Sant’Antioco, in P. BERNARDINI, R. D’ORIANO, P.G. SPANU (a cura di), Phoinikes B Shrdn. I Fenici in Sardegna-nuove acquisizioni (a cura di ), Cagliari 1997, pp. 115-116.

- C. TRONCHETTI, La tomba 12 AR della necropoli punica di Sant’Antioco = QuadCa 2002, pp. 143-171.

Periodicals and magazines

- BA = Bollettino d’Arte, Roma, 1907 e ss.

- BAS = Bullettino Archeologico Sardo, Cagliari, I, 1855 e ss.

- NBAS = Nuovo bullettino archeologico sardo, Sassari, I, 1984 e ss.

- NSc = Atti dell'Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Notizie degli scavi di antichità, Roma 1944- Già: Atti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei. Notizie degli scavi di antichità, Roma 1876-1920 (fa parte di Atti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei. Memorie della Classe di Scienza Morali, Storiche e Filologiche, Roma 1876). Poi: Atti della Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Notizie degli scavi di antichità, Roma 1921-1939. Poi: Atti della R.eale Accademia d’Italia. Notizie degli scavi di antichità, Roma 1940-1943.

- QuadCa = Quaderni della Soprintendenza Archeologica per le Province di Cagliari e Oristano, Cagliari, I, 1986 e ss.

- RSF = Rivista di Studi Fenici, Roma, 1973 ess.

VR

VR