Weapons and armours of medieval knights

The fortified complex of Monreale is located on top of a hillock in the Municipality of Sardara (southern Sardinia), where it was built, presumably on structures from an earlier period, during the second half of the thirteenth century, to guard the southern border of the District of Arborea, to which it belonged. It held the dual function of border and residential castle and housed a garrison of soldiers which kept watch not only over the region, but also over the Judge and his family who often stayed there. These soldiers were armed according to the standards of medieval times.

The weapons and armours of the medieval knight evolved over the centuries in order to adapt to the transformation of the art of war.

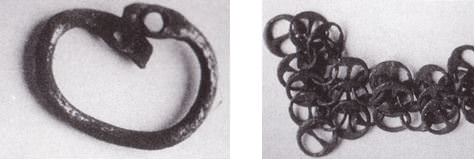

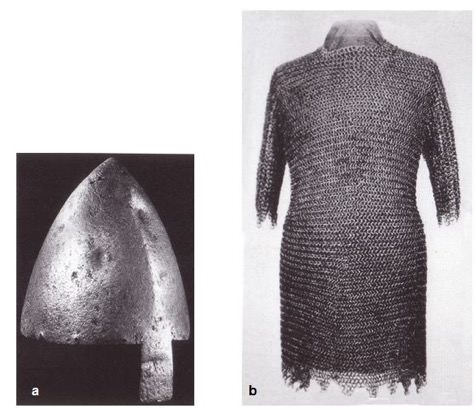

In the middle of the twelfth century the warrior wore a long tunic to his knees, over which he slipped on a leather or canvas chainmail, covered with iron rings tightly connected to each other (fig. 1). The head was protected by a metal cone helmet (fig. 2 a), provided with a protective sheet for the nose, but which left the face uncovered. The legs were covered with shin guards. The defensive armour was completed by a large wood shield, circled in iron and almond shaped. His defensive weapons were the sword and the lance.

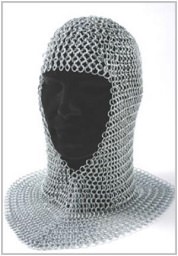

During the thirteenth century an iron chainmail called "hauberk" was used (fig. 2 b), with a combined or separate hood (the so-called camail, fig. 3). The hauberk protected the soldier from blows from the tip of the sword, but was not enough for the more violent ones from a lance or from mauls.

Under the hauberk he wore a padded tunic to cushion the blows and to prevent injuries and over this he wore another fabric tunic (called tabard, fig. 4), sleeveless and with splits at its sides, which sheltered the hauberk from sun and rain. This tabard was fastened by his belt, on which he hung his sword. During this period the conical helmet was replaced by the bassinet helmet of conical-cylindrical shape; this was completely closed but provided with holes to allow breathing and listening with two horizontal openings for the eyes (fig. 5). Subsequently the bassinet helmet evolved into the great helm, similar but considerably heavier, so much so that the knight had to protect his head with a cap of cloth and leather in order to wear it, onto which he added a “cupola” to cover the top of his skull and a camail to protect the throat (fig. 6).

Finally, the warrior’s legs were protected by knee pads and shin guards. The shield also began to evolve, its dimensions were reduced to make it more manageable. On horseback, the man-at-arms bore the lance (about four metres long) vertically, with the end of the pole secured to the right stirrup; in action, however, he held the pole under his armpit and stood on his stirrups so as to sustain the impact with the enemy.

During the fourteenth century the cavalry was no longer the undisputed master of the battlefield, as the infantry began to assert itself, with its main weapons consisting of the crossbow and bow.

During the fourteenth century, a cloak of precious cloth (called surcoat) began to be used; this was sleeveless, tight and with a padded chest covering the hauberk, which at this stage only reached to mid-thigh. The sword belt was buckled onto it. The shield was small and triangular. The use of iron plates to protect the torso and limbs also spread among horsemen. Because of the weight and inconvenience of the closed helmet it began to be used solely at the moment of battle, whilst it was replaced by the cervellière, a kind of steel skullcap and, later, with a new type of helmet, the barbut helm at other times (fig. 7). It was also widely used by the infantry. Between the second half of the fourteenth century and the first decade of the fifteenth, the barbut helm was joined by the bassinet (fig. 8), usually provided with a small camail called gorget.

Armours in the fourteenth century were more durable and lighter than those in chain mail and were well suited to the new way of fighting on foot used by the cavalry.

In fact, in order to better withstand the sharp and heavy infantry weapons, the horses were left behind and the knights, having shortened their lances, marched against the enemy with the support of the crossbowmen and archers.

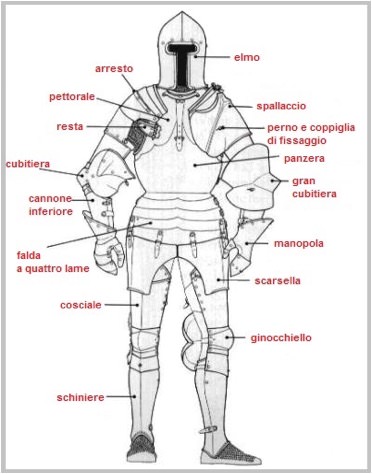

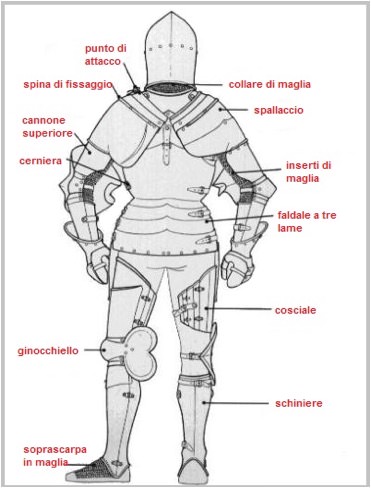

During the fifteenth century the men-at-arms were increasingly engaged in ground fighting and needed a durable armour which covered their body completely but left freedom of movement: armourers skilfully modelled the armour on the wearer, creating robust products weighing less than 25 kilos (figs. 9-10).

The Italian helmet of the first half of the fifteenth century changed by becoming smaller, lighter and equipped with a mobile visor, which allowed seeing and breathing easily. The helmet visor could be of the "hounskull" or “dog-faced” types. In the fifteenth century the helmet was considered a separate piece and the armour was either completed by the helmet or by a bassinet or a barbut. The habit of only wearing a helmet during battle still persisted during the fifteenth century, whilst cloth caps or hats were used at all other times.

With the introduction of firearms during the second half of the sixteenth century, the art of the armourers rapidly declined.

Bibliografia

- J. ARMANGUÉ I HERRERO, Uomini e guerre nella Sardegna medioevale, Mogoro 2007.

- E. POMPONIO, I Templari in battaglia, Tuscania 2005.

- A. MONTEVERDE, E. BELLI, Castrum Kalaris. Baluardi e soldati a Cagliari dal Medioevo al 1899, Cagliari 2003.

- VIOLLET LE DUC, Encyclopédie Médiévale, Tours 2002.

- MONTEVERDE, G. FOIS, Milites. Atti del Convegno, Saggi e Contributi (Cagliari, 20-21 dicembre 1996), Cagliari 1996.

VR

VR