The basilica of Sant'Antioco Martyr

The basilica of Sant'Antioco has been known since the Middle Ages. In 1089, what was then called the Monastery of Sant 'Antioco was donated by Giudice Constantine II of Cagliari to the Vittorini monks of Marseilles, together with the church reconsecrated by Bishop Gregorio of Sulky in 1102. The island of Sant'Antioco, however, remained virtually uninhabited until the eighteenth century due to the incursions of the Saracens, although in 1615 the Archbishop of Cagliari Francisco De Esquivel ordered a reconnaissance in the underground sanctuary, in order to bring to light the alleged relics of the saint which were found in a sarcophagus-altar at the entrance of the catacombs (fig. 1).

It is not known exactly if the so-called martyrium, built where the basilica stands today, may be identified with the ancient cathedral, that is, with the true episcopal see, but all the information that has reached us from the Byzantine Age and from the early Middle Ages seems to show that, at least since the seventh century, the martyrium and the cathedral were the same thing.

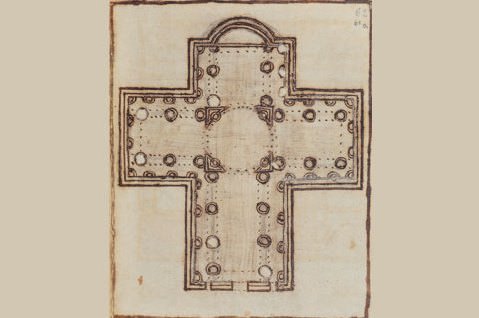

The building that you can see today has changed over the centuries and currently has a longitudinal plan which hides the ancient structures that testify that the basilica of Sant'Antioco was originally a "Greek cross" building: a "cube" with a dome in the centre, with four barrel-vaulted radiating branches. The pattern is typical of the so-called quadrifida (divided into four sections) Martyrium, similar to the late ancient plan of San Saturno in Cagliari and similar to the Byzantine structures of the church of San Giovanni di Sinis (figs. 2-3).

It is possible to enter the church through two entrances: one is the portal opened in the seventeenth century along the north flank of the medieval church, the other the portal on the facade (figs. 4-5).

The medieval facade was probably built on the ruins of the ancient Phoenician-Punic or Roman walls of Sulky. This masonry is in fact made up of large ashlar trachyte blocks identical to those of the fortification structures of the ancient city. The dome is supported by an octagonal drum at the base of which there are small sculptures, in the shape of a tortoise shell (the two pairs to the West) and a lion’s paw (the two couples to the East) (figs. 6-8).

In Christian iconography, the lion takes on a dual significance, both positive and negative; more frequently, it plays an apotropaic role, i.e. with the function of driving away evil forces, but it can also represent the figure of Christ. The turtle is an ancient symbol of Indian cosmology, but also the animal which fights against a cock in the mosaics of Aquileia, the latter figure alludes to Christ.

Bibliografia

- R. CORONEO, La basilica di Sant’Antioco, in R. LAI, M. MASSA (a cura di), Sant’Antioco da primo evangelizzatore di Sulci a glorioso protomartire “Patrono della Sardegna”, Sant’Antioco 2011, pp. 87-97.

- R. MANNO, “Chiesa parrocchiale di S. Antioco”, in P. G. SPANU (a cura di), Materiali per una topografia urbana. Status quaestionis e nuove acquisizioni. V Convegno sull’archeologia tardoromana e medievale in Sardegna (Cagliari-Cuglieri, 24-26 giugno 1988), Oristano, S’Alvure, 1995, p. 96.

- R. SERRA, La chiesa Martyrium dall’impianto monumentale al 1102, in L. PORRU, R. SERRA, R. CORONEO, Sant’Antioco. Le Catacombe, il Martyrium, i frammenti scultorei, Cagliari 1989, pp. 87-101.

VR

VR