Basilica of San Saturnino

- Early Christian Age, IV-VII / VIII century A.D.

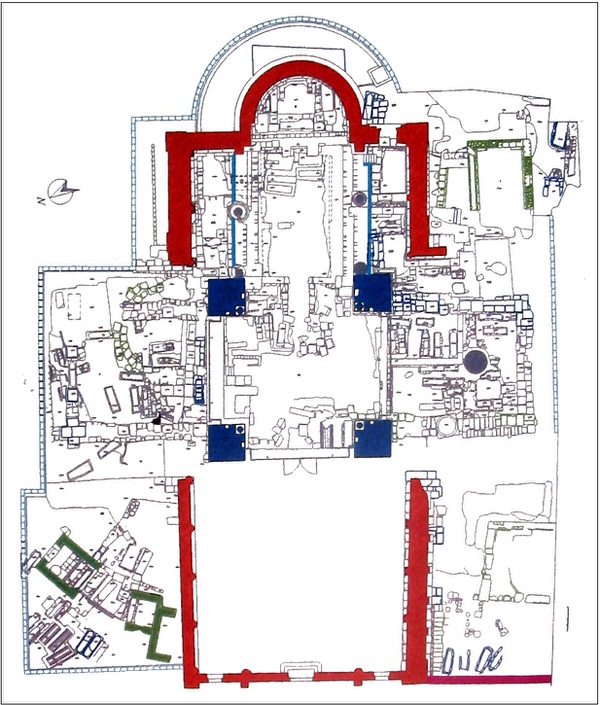

The archaeological site of San Saturnino is located in the eastern part of the city of Cagliari, an area which in ancient times stood outside the city limits and was part of the necropolis extending east of the town, from today's Viale Regina Margherita up to the Bonaria hill. Here you can still see the surviving evidence of the necropolis and the Basilica dedicated to the martyr Saturnino (fig. 1).

The oldest presently known structure in the area is a quadrangular building, whose function is not yet clear, standing in the south-east area of the necropolis. In addition, a stretch of isodomic wall in ashlar, dating back to the IV-III century BC or to the late-republican Age, was found under the foundations of the northern transept of the church. Tombs and funerary remains of buildings from both the Roman period and the late ancient period are still visible around this place of worship: the necropolis alternated open spaces, with graves of various types (pit tombs, “a cupa” tombs, underground sarcophagi; fig. 2) with funeral buildings of various sizes, made of limestone ashlars and bricks, sometimes with mosaic floors (fig. 3); the burials were placed inside, particularly graves covered with bricks and/or small stones, with either flat-placed tiles or slabs or more rarely Capuccina-style. The layout of the internal roads, which the orientation of the buildings was connected to, is still unclear.

The remains of some mausoleums are also preserved under the nearby Church of St. Lucifero, built during the seventeenth century as a result of the searches for the holy bodies and the discovery of the alleged tomb of Bishop Lucifero of Cagliari, the defender of orthodoxy and an uncompromising opponent of the Arians, who lived in IV century: this consists of a structure originally made up of three funerary rooms known as "underground churches" or chapels of St. Lussorio, of Rude and St. Lucifero (fig. 4). The seventeenth-century chronicles allow us to trace the original shape consisting of a small quadrangular room connected to a rectangular room with pillars and arcosolia on the walls, which housed burial layers, while others were arranged over various levels under the floor and marked by inscriptions, including mosaics. The 2nd church is still fully visible (fig. 5) - whose flattened barrel vault dates back to the seventeenth century and the floor to the 50s of the twentieth century - as is the access corridor to the 1st church (buried under the former Technical Institute) while the 3rd, profoundly altered, can be assumed was located where the chancel of the present church is.

Saturnino was laid in the necropolis, probably at the beginning of the fourth century, according to sources in a "small crypt", perhaps attributable to a large apse discovered in the northern area (fig. 6); some scholars identify this as the "basilica" seen by Fulgenzio, bishop of Ruspe exiled in Cagliari during the first half of the sixth century.

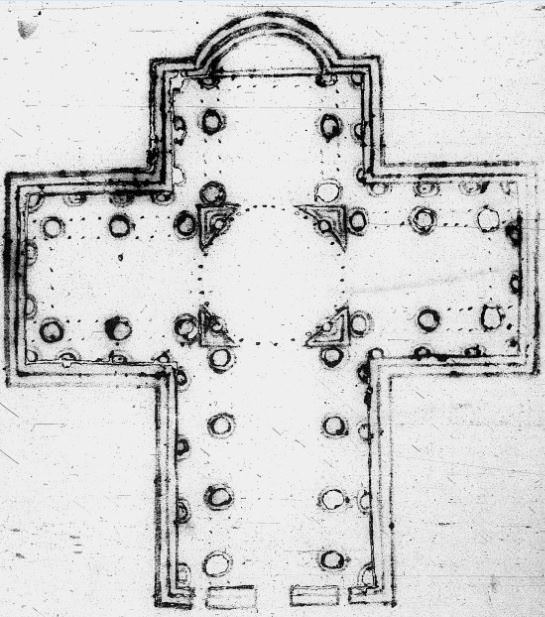

The church which can currently be seen is the result of the changes, restructuring and decline which occurred over the centuries: the first construction dates back to the Byzantine era, between the second half of the sixth and the early seventh centuries, with the domed body (fig. 7), cross plan and three nave transepts, of which only the central structure and residues of its rectangular apse remain.

The dome is joined to the square room by half-dome squinches , defined by round arches which rest on pillars with red marble cloisonné columns (fig. 8). The construction deeply changes the layout of the necropolis, which continues to be used, with the demolition of the previous funeral rooms located in the area identified in its construction and the levelling with the materials obtained from the demolition itself, also used for the church masonry.

New burials therefore occur in the spaces thus created, whose position is affected by the transformation of the area: whilst late Roman graves are oriented according to the buildings which contain them, Byzantine and early medieval ones which are placed in open spaces are west-east oriented and arranged in relation to the domed body, which they sometimes rest against.

As is proved by some documents from the Court of Cagliari, during the Giudicato period the church was given by the judge to the monks of St. Vittore of Marseille who, between 1089 and 1119, restructured it according to pre-Romanesque models, keeping the central domed body and reconstructing the four transepts, of which only the eastern remains intact, with three naves and on which perhaps the main apse was built, faced in limestone with hints of two-colour paint in the apse, a middle barrel vaulted nave and the cross-vaulted aisles (figs. 9-10). The Provencal workers used a great deal of reclaimed material such as capitals, columns, architectural fragments, inscriptions and memorial stones. All the burials and early Middle Age contexts were in turn obliterated by the flooring during the “Vittorina” period.

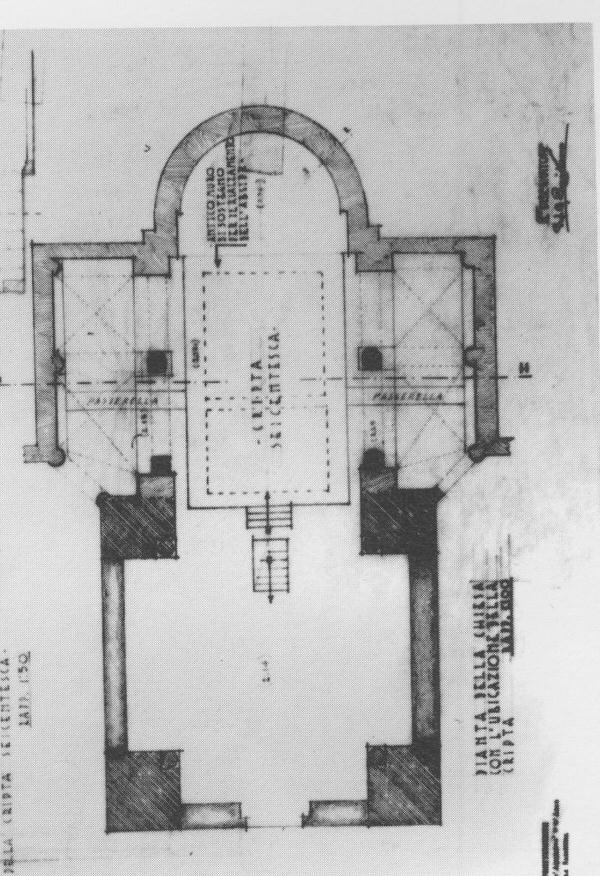

During the seventeenth century, the already partially decrepit area inside and outside the church was devastated by the search for the bodies of saints, following which a crypt was built along the longitudinal axis of the church, now partially preserved, which was originally accessible by a staircase (fig. 11). These excavations, conducted without any scientific method, but simply in order to bring to light the largest possible number of alleged martyrs’ relics, have irrevocably altered the oldest layers, thereby creating considerable difficulties for modern scholars to understand and reconstruct the site.

Bibliografia

- J. ALEO, Successos generales de la Isla y Reyno de Sardeña. Manoscritto autografo conservato nella Biblioteca Universitaria di Cagliari, Caller 1684.

- D. BONFANT, Triumpho de los Santos del Reyno de Cerdeña. Calari: typis haeredum Ioannis Mariae Galcerin, 1635.

- J.F. CARMONA, Alabanças de los Santos de Cerdeña. Caller (manoscritto Conservato presso la Biblioteca Universitaria di Cagliari), 1631.

- A.M. CORDA, Le iscrizioni cristiane della Sardegna anteriori al VII secolo. Studi di antichità cristiana, LV. Città del Vaticano 1999.

- R. CORONEO, L’architettura romanica in Sardegna dalla metà del Mille al primo ‘300. Nuoro 1993.

- R. CORONEO, La basilica di San Saturnino a Cagliari nel quadro dell’architettura mediterranea del VI secolo, in San Saturnino. Patrono della città di Cagliari nel 17. centenario del martirio. Atti del Convegno (Cagliari, 28 ottobre 2004). S.l. 2004, pp. 55-83.

- R. CORONEO, Sarcofagi marmorei del 3.-4. secolo d'importazione ostiense in Sardegna, in R.M. Bonacasa, E. Vitale eds., La cristianizzazione in Italia fra tardoantico e altomedioevo”. Atti del IX Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Cristiana (Agrigento, 20-25 novembre 2004), Palermo 2007, pp. 1354-1368.

- R. CORONEO, R. SERRA, Sardegna preromanica e romanica, Milano 2004.

- P. CORRIAS, S. COSENTINO, Ai confini dell’Impero. Storia, arte e archeologia della Sardegna bizantina, Cagliari 2002.

- M. DADEA ET ALII. Arcidiocesi di Cagliari. Chiese e arte sacra in Sardegna, 3, Sestu 2000.

- R. DELOGU, L’architettura del Medioevo in Sardegna, Roma 1953.

- R. DELOGU, Vicende e restauri della basilica di S. Saturno in Cagliari, in Studi sardi, 12-13, 5-32.

- F. DESQUIVEL, Relaciòn de la invenciòn de los Cuerpos Santos que en los años 1616, 1615, 1616, fueron hallados en varias Iglesias de la Ciudad de Caller y su Arçobispado, Napoles 1617.

- S. ESQUIRRO, Santuario de Caller, y verdadera istoria de la inbencion de los Cuerpos santos hallados en la dicha Ciudad y su Arçobispado. Calari: typis haeredum Ioannis Mariae Galcerin, 1624.

- I.F. FARA, Opera, 1-3, a cura di E. CADONI, traduzione italiana di M.T. Laneri, Sassari 1992.

- T.K. KIROVA (ed.), Arte e Cultura del ‘600 e del ‘700 in Sardegna, Napoli 1984.

- A. MACHIN, Defensio Sanctitatis Beati luciferi Archiepiscopi Calaritani. Calari: typis haeredum Ioannis Mariae Galcerin, 1639.

- R. MARTORELLI, Le aree funerarie della Sardegna paleocristiana, in P.G. SPANU ed., Insulae Christi: il Cristianesimo primitivo in Sardegna, Corsica, Baleari. Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale: scavi e ricerche, 16, Cagliari-Oristano 2002, pp. 315-340.

- R. MARTORELLI, Gregorio Magno e il fenomeno monastico a Cagliari agli esordi del VII secolo, in “Per longa maris intervalla. Gregorio Magno e l’Occidente mediterraneo fra tardoantico e altomedioevo”. Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Cagliari, Pontificia Facoltà Teologica della Sardegna, 17-18 dicembre 2004), Cagliari 2006, pp. 125-158.

- R. MARTORELLI, Committenza e ubicazione dei monasteri a Cagliari in età medievale, in L. PANI ERMINI ed., Committenza, scelte insediative e organizzazione patrimoniale nel medioevo. (De Re Monastica - I). Atti del Convegno di studio (Tergu, 15-17 settembre 2006), Spoleto 2007, pp. 281-323.

- R. MARTORELLI, Martiri e devozione nella Sardegna altomedievale e medievale, Cagliari 2012.

- R. MARTORELLI, D. MUREDDU (eds.), Archeologia urbana a Cagliari. Scavi in Vico III Lanusei (1996-1997), Cagliari 2006.

- D. MUREDDU ET ALII, Sancti innumerabiles. Scavi nella Cagliari del Seicento: testimonianze e verifiche, Oristano 1988.

- D. MUREDDU ET ALII, Alcuni contesti funerari cagliaritani attraverso le cronache del Seicento, in Le sepolture in Sardegna dal IV al VII secolo. Atti del IV Convegno sull’archeologia tardoromana e medievale (Cuglieri, 27-28 giugno 1987). Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e ricerche, 8, Oristano 1990, pp. 179-206.

- D. MUREDDU, G. STEFANI, Scavi “archeologici” nella cultura del Seicento, in T.K. KIROVA ed., Arte e Cultura del ‘600 e del ‘700 in Sardegna, Napoli 1984, pp. 397-406.

- A.M. NIEDDU, La pittura paleocristiana in Sardegna: nuove acquisizioni, in Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana LXXII, 245-283.

- A.M. NIEDDU, L’arte paleocristiana in Sardegna: la pittura, in P.G. SPANU ed., Insulae Christi: il Cristianesimo primitivo in Sardegna, Corsica, Baleari. Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale: scavi e ricerche, 16. Cagliari-Oristano 2002, pp. 365-386.

- L. PANI ERMINI, Ricerche nel complesso di S. Saturno a Cagliari, in Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia Romana d'Archeologia, 55/56, 111-128.

- L. PANI ERMINI, Il complesso martiriale di San Saturno, in P. DEMEGLIO, C. LAMBERT eds., La Civitas christiana. Urbanistica delle città italiane fra tarda antichità e altomedioevo. Aspetti di archeologia urbana. Atti del I Seminario di studio (Torino 1991). Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Quaderni, 1, Torino 1992, pp. 55-81.

- L. PANI ERMINI, Contributo alla conoscenza del suburbio cagliaritano "iuxta basilicam sancti mortyris Saturnini", in “Sardinia antiqua”. Studi in onore di Piero Meloni in occasione del suo settantesimo compleanno, Cagliari 1992, pp. 477-490.

- A. PIRAS, Fulgentius von Ruspe, Epist. 13,3: thapsensis oder tharrensis?, Vigilia Christianae, LV, 156-160.

- A. PIRAS, Lingua et ingenium. Studi su Fulgenzio di Ruspe e il suo contesto. Ortacesus 2010.

- A. PISEDDU, Francisco Desquivel e la ricerca delle reliquie dei martiri cagliaritani nel secolo XVII, Cagliari 1997.

- D. SALVI, Cagliari: San Saturnino, le fasi altomedievali, in P. CORRIAS, S. COSENTINO eds., Ai confini dell’Impero. Storia, arte e archeologia della Sardegna bizantina, Cagliari 2002, pp. 225-229.

- D. SALVI, Cagliari: l’area cimiteriale di San Saturnino, in P.G. SPANU ed., Insulae Christi: il Cristianesimo primitivo in Sardegna, Corsica, Baleari. Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale: scavi e ricerche, 16, Cagliari-Oristano 2002, pp. 215-223.

- G. SPANO, Guida della città di Cagliari, Cagliari 1861.

- P.G. SPANU, Lo scavo archeologico di piazza S. Cosimo a Cagliari, in P. DEMEGLIO, C. LAMBERT eds., La Civitas christiana. Urbanistica delle città italiane fra tarda antichità e altomedioevo. Aspetti di archeologia urbana. Atti del I Seminario di studio (Torino 1991). Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Quaderni, 1, Torino 1992, pp. 83-118.

- P.G. SPANU, La Sardegna bizantina tra VI e VII secolo. Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e Ricerche, 12, Oristano 1998.

- .G. SPANU, Martyria Sardiniae. I santuari dei martiri sardi. Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale. Scavi e Ricerche, 15, Oristano 2000.

- P.G. SPANU, Le fonti sui martiri sardi, in P.G. SPANU ed., Insulae Christi: il Cristianesimo primitivo in Sardegna, Corsica, Baleari. Mediterraneo tardoantico e medievale: scavi e ricerche, 16, Cagliari-Oristano 2002, pp. 177-198.

- R. TURTAS, Il monachesimo in Sardegna tra Fulgenzio di Ruspe e Gregorio Magno, in Rivista di Storia della Chiesa in Italia XLI, 92-110.

VR

VR