Nuragic village of Su Nuraxi

- Nuraghic period, XV-VI century B.C.

Su Nuraxi, one of the most important, majestic Nuraghi of the so-called “Nuragic Civilisation” is located close to Barumini, at the foot of the Parco della Giara.

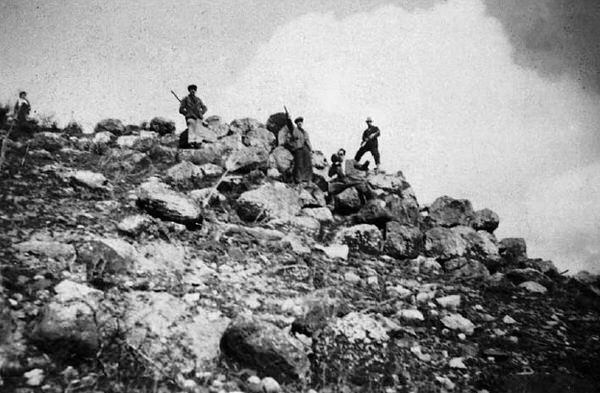

The most ancient photographs of Su Nuraxi, in a state of collapse and looking like a small hill, dates to 1937 (fig. 1).

The first description of the monument dates to 1938, written by the archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, who discovered the type and layout of the nuraghe (fig. 2).

The archaeological area includes a complex Nuraghe, comprising a central tower and four perimeter towers, a perimeter wall and a Nuragic and Punic-Roman dwelling area. The Nuraghe, made from basalt and marl blocks, rises majestically on a high plain, from where it dominates the surrounding landscape (fig. 3).

The systematic dig of the settlement (fig. 4) carried out under the leadership of Lilliu from 1951 to 1956, allowed recognition of the various phases of life that bore witness to the occupation of the site from the mid 2nd millennium B.C. (1600 B.C. circa) until the times of Punic and Roman inhabitation (3rd century A.D.).

According to most experts, the Nuraghi were buildings used for multiple purposes, built by a tribal society and destined to control the territory and its resources. The simple nuraghi were used to supervise fertile areas, communications routes, and coastal ports etc. Complex nuraghi were used to control territorial districts and were probably used as collection and distribution centres for goods; these buildings were often constructed as real fortresses where perishable foodstuffs were preserved, water resources were kept and people and animals could find temporary refuge (fig. 5).

Giovanni Lilliu, the renowned expert who dug and studied the area of Su Nuraxi, divided the birth and development of the archaeological complex into five different phases: In the first phase, about the 16th-14th centuries B.C., the simple Nuraghe was built; in the second phase, between the end of the 15th and the 13th centuries, B.C., the isolated tower was turned into a complex nuraghe, with the addition of a bastion with four perimeter towers and a perimeter wall; in this phase, the first residential area was built, of which few traces now remain. In the third phase, between the 12th and 10th century B.C., the wall around the bastion was rebuilt, access to the monument at ground level was closed and a raised entrance was created. The circular layout hut village was also developed in this period. During the fourth phase, between the 9th and the 6th century B.C. The monument was abandoned and the sector and central courtyard hut village was created. In the fifth phase, from the 6th/5th century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D., the Punic-Roman dwelling area was developed, with an adaptation of the previous Nuragic huts and the creation of new structures; the nuraghe was used once again during this period for dwelling, funeral and worship purposes.

The central tower now has a height of about 14 metres and two chambers, one above the other. It was originally over 18 metres high, and had three chambers; it was possible to reach the terrace from the top one, that had a walkway supported by corbels. The latter, which have now collapsed from their original position, are currently on show along the perimeter of the archaeological area (figs. 6, 7).

The bottom chamber has an internal diameter of approximately 5 metres and a height of 8 metres; it has two large niches, a kind of built-in cupboard and storeroom, and more than 4 metres above the floor, the start of the staircase, that was originally reached by a mobile wooden or rope staircase, that led to the upper two chambers. The quatrefoil bastion was added attached to the more ancient nuraghe structure: four towers united by straight curtain walls placed at the top of a square figure. The towers were originally about 14 metres high, with two chambers one above the other and a middle silos; the bottom chambers had two kinds of embrasures; the higher embrasures could be reached from a wood walkway. The bastion and the towers were crowned with jutting corbels, like the keep. The bastion held a semi-circular courtyard, with a well inside it (fig. 8).

The nuraghe was also protected by a perimeter wall, the bulwark, that had eight towers, that could be accessed via two narrow entrances. A third door was placed in the North-East extension of the walls. These entrances were defended by embrasures in the towers and the perimeter wall.

The area of Su Nuraxi grew up between the Recent Bronze Age and the Roman Era. There are few traces remaining from the Recent Bronze Age. In the Final Bronze Age, there was a large dwelling area comprising circular huts made from basalt blocks, originally covered with sticks and branches. One of these was a large circular structure with a bench around the internal perimeter, known as the “capanna delle assemblee o curia” of Barumini (fig. 9).

During the Iron Age, the monument and the dwelling area were abandoned. A large, complex residential area was built on top of the village ruins, built according to new organisational criteria and a rational project: the houses from this period were sector-types, or ones with a central courtyard, and with rectangular rooms, but there were also isolated round buildings. Some sector houses also have a small circular room with a bench and central basin, a so-called “rotonda” that was perhaps used for domestic worship (fig. 10).

During the long Punic-Roman period many structures were used again or altered, but new ones were also built; the Nuraghe was also used again, for burial, dwelling and sacred purposes. The area of Su Nuraxi was still frequented in the 6th and 7th centuries A.D., before being finally abandoned. The collapse of the top parts into the courtyard and external areas, the overlapping of items from various periods, and the accumulation of natural deposits have brought the monument to be abandoned, hidden beneath a neglected and isolated artificial hill. UNESCO recognised Su Nuraxi as part of World Heritage in 1997 (fig. 11).

It was therefore no surprise that the “fallen giant”, as Lilliu called it, received the prestigious UNESCO acknowledgement for the unique nature of the monument, a masterpiece of human creative genius and exceptional proof of a civilisation that disappeared. Today, in spite of the fact that modern digs have brought to light other imposing Nuraghi, Barumini remains “the nuraghe” par excellence, an ancient but modern symbol of the island.

Bibliografia

- ATZENI E., In ricordo di Giovanni Lilliu, in L'isola delle torri: Giovanni Lilliu e la Sardegna nuragica. Catalogo della mostra, pp. 31-34.

- LILLIU G., Il nuraghe di Barumini e la stratigrafia nuragica, in Studi Sardi, XII-XIII (1952-1954), Sassari 1955.

- LILLIU G., ZUCCA R., Su Nuraxi di Barumini, Sardegna archeologica, Guide e Itinerari, Sassari 1988.

- MURRU G., Su Nuraxi di Barumini 1950/2000. Le immagini del sito archeologico più famoso della Sardegna dai primi scavi al riconoscimento internazionale dell'UNESCO, Cagliari 2000.

- MURRU G., Barumini. Su Nuraxi e il villaggio nuragico, Fondazione Barumini Sistema Cultura, 2007.

- SANTONI V., Il nuraghe Su Nuraxi di Barumini, Guide e Studi, Quartu Sant’Elena 2001.

VR

VR