The frescoes in the rock church

The tombs in the domus de janas necropolis of Sant’Andrea Priu, dug into an outcrop of volcanic rock, is proof of the presence of man in this area since the Neolithic age.

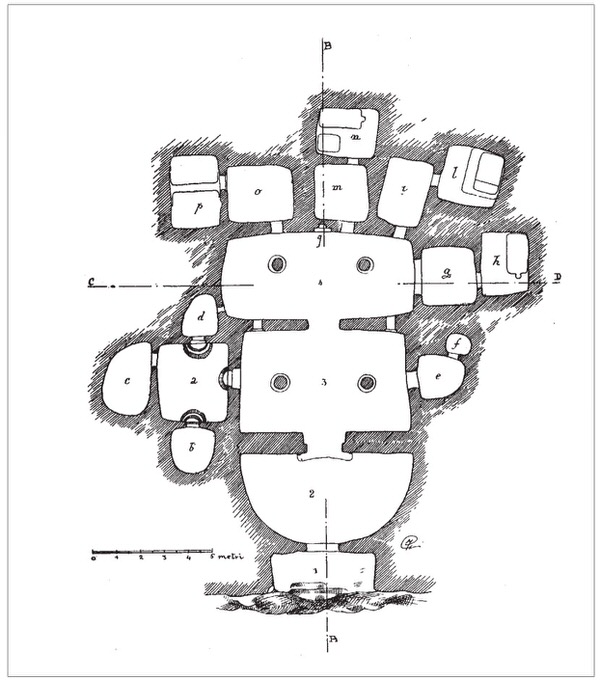

Tomb VI, known as the “Tomba del Capo” (fig. 1), was used for Christian worship in two separate moments, reaching the present days as the consecrated church of Sant'Andrea.

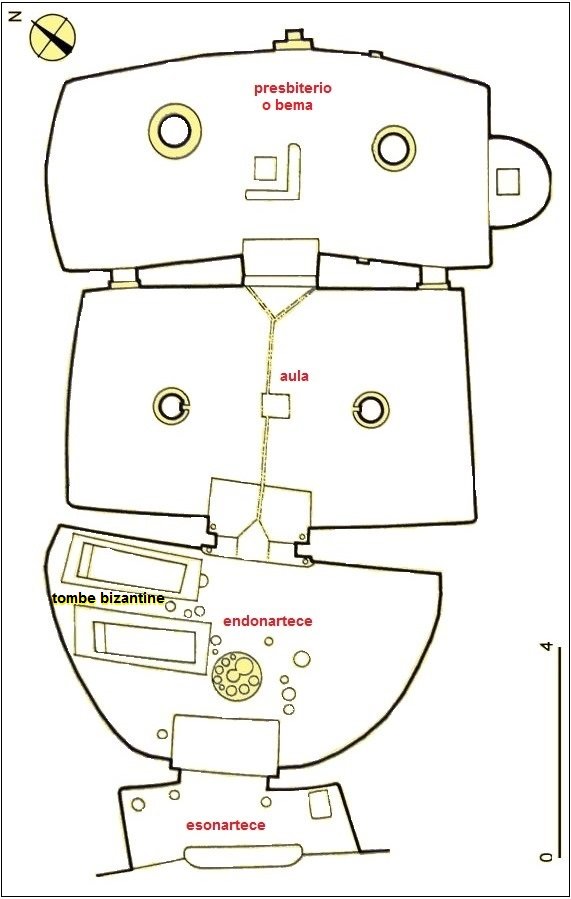

The tomb has eighteen rooms, the three largest arranged in length (fig. 2) that have undergone significant modifications during the Paleo-Christian, Byzantine and Medieval ages. The room nearest to the entrance was a narthex, used to welcome those who had not yet been baptised, the central one was used as a room for the faithful who had already been baptised and the third was used as the presbytery (bimah) i.e. the space reserved for priests.

The entrance (endo-narthex or external narthex) was sub-rectangular, created in the original prehistoric ante-cell; an architraved door leads into a semi-circular room (esonarthex or inner narthex) which was 7 metres in diameter, where the floor has several hollows linked to prehistoric rituals that were carried out in honour of the deceased (fig. 2).

This then leads into the trapezoid shaped room (largest size 7.50 metres, smallest 6.75 metres, sides of 4 metres), with channels cut into the floor, connected to each her, that flow into the endo-narthex. The flat ceiling is about 3 metres high and is supported by two pillars that grow narrower towards the top. A door leads into a sub-rectangular room of 7.70 metres by 3.30 metres (bimah, fig. 2) with a flat roof supported by two pillars that are narrower at the top. Where the altar stood, the ceiling has a square skylight cut into it (1.50 x 2 metres) that reaches the ground above, having been cut through about 5 metres of rock.

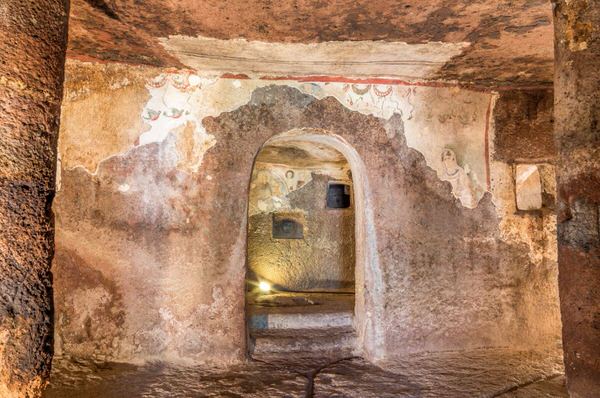

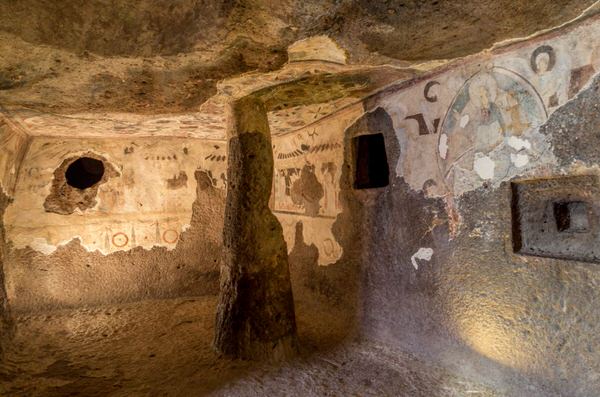

The walls and ceiling of the middle chamber and innermost chamber are decorated with frescoes, some of which are missing in gaps (figs. 3-4).

The dates suggested by experts for the paintings lie between the 4th and 6th centuries A.D., while in the bimah, they are dated, with some doubt, to the second half of the 8th century A.D. The two tombs dug out of the floor of the endo-narthex can be attributed to the Byzantine Age.

Bibliografia

- BONINU A., SOLINAS M. (a cura di), La necropoli di Sant'Andrea Priu, Macomer, 2000.

- CAPRARA R., La necropoli di Sant'Andrea Priu, Sardegna Archeologica. Guide ed itinerari, Sassari 1986, pp. 3-73.

- CORONEO R., SERRA R., Sardegna preromanica e romanica, Milano 2004, pp. 61-68.

- CORONEO R., Chiese romaniche della Sardegna. Itinerari turistico-culturali, Cagliari, 2005, pp. 55-56.

- TARAMELLI A., Fortezze, recinti, fonti sacre e necropoli preromane nell'agro di Bonorva, collana Monumenti antichi dei Lincei, Roma, 1919, coll. 765-904.

VR

VR