Corsairs and pirates in the Mediterranean

The terms “corsair” and “pirate” are mistakenly used as synonyms.

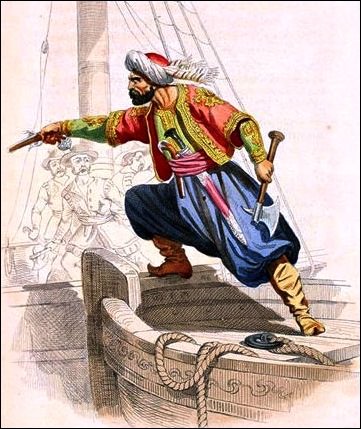

The “corsair” was the captain of an armed ship, authorised by a State in war to attack and rob an enemy vessel, to damage sea trade (fig. 1). The authorisation was granted through so-called “lettere di corsa (travel letters)”. This practice started in the XII century, peaked in the XVI and ended in the mid XIX century.

Meanwhile, “Pirates” sailed the seas to attack and rob ships of any nationality, for their own profit, with no authorisation.

The Mediterranean was raided by the Arabs (also called Saracens) as of the VIII century. But the phenomenon was especially strong in the XVI century, after the Ottoman power had expanded into the western Mediterranean basin.

The members of the Ottoman navy were often called “Barbarian pirates”. These were Muslim sailors belonging to various ethnic groups (Arabs, Berbers, Turks and European Renegades). They were present all over the Western Mediterranean and along the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa. They moved out from the strongholds present on the coasts of North Africa (Tunis, Tripoli, Algiers), in the zones that the Europeans called "Barbary Coast" or Barbarian states (the inhabitants of the North African regions were, in fact, called “Berbers”).

The goal of the Barbarian corsairs were ships, military or civil, sailing the Mediterranean coming from European countries.

For the Italian populations the most ferocious period of Barbarian activities was the XVI century when the Barbarian corsairs, allied with the French, addressed their raids at Southern Italian fleets and coasts, dominated by the King of Spain at the time.

The Barbarian corsairs did not just rob ships. They often raided territories overlooking the sea. The numerous coastal towers present along Italian coasts were built to prevent those attacks. They raided the mainland to kidnap people to be slaves or to free them on payment of a ransom.

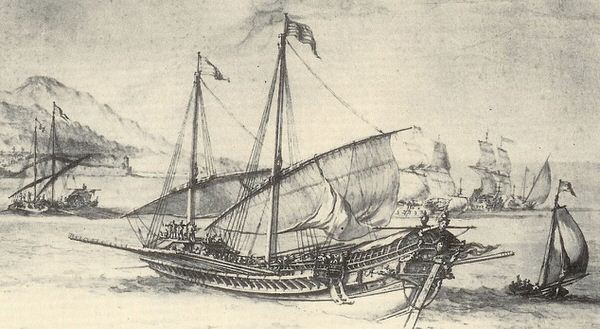

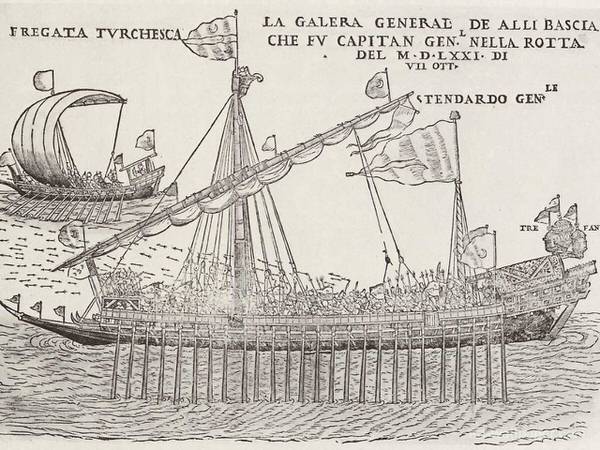

In the XVI century, the ships used by the Christian and Muslim fleets were galleys (figs. 2-3). They had a long (50 or 55 metres) narrow (about 5 metres) hull, with a single order of oarsmen arranged in two parallel rows. They were fast, agile boats which, when used for military purposes, used lateen sails.

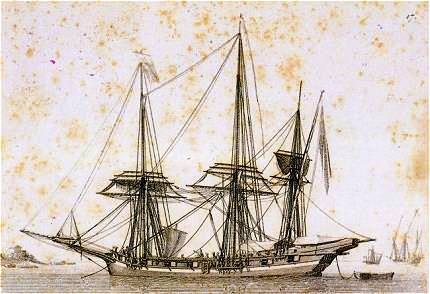

Along with galleys there were another two types of boat: feluccas (fig. 4) and zebecs (fig. 5). The former were no more than twenty metres long, wider than galleys, equipped with several sails and with eight or twelve oars; the latter had a large hull and were armed with several guns.

Corsair activities mainly took place from spring till autumn and, to a lesser extent, in winter. The galleys and other rowing boats were used in summer, while sailing ships were used in the bad season to exploit the strong winter winds.

Bibliografia

- AA.VV. a cura di D. Gnola, Corsari nel nostro mare. Catalogo della mostra (5 luglio- 7 settembre 2014, Cesenatico),Bologna 2014.

- I. MARONGIU, Corsari e pirati nel mare d'Ogliastra. Il Moro nella storia e nella tradizione orale sarda, Arzana 2011.

- M. LENCI, Corsari. Guerra, schiavi, rinnegati nel Mediterraneo, Roma 2006.

- D. OLLA, M. TORENO, La pirateria nel Mediterraneo, in ASSOCIAZIONE SI-CUTERAT, Museo delle Torri e dei Castelli della Sardegna. Collezione Monagheddu Cannas, Sassari 2003, pp. 26-29.

- S. BONO, I corsari barbareschi, Torino 1975.

- J.J. BAUGEAN, Recueil de petites marines, Paris 1817.

VR

VR