Hortus Simplicium

In the Middle Ages, and in addition to being religious centres, monasteries played an important role in social and cultural life. In particular, Benedictine monasteries combined prayer with manual work, and contributed to the economic recovery of the countryside areas.

In fact, the monks were the only people who still held classical knowledge and managed to pass on centuries of this knowledge through their scriptoria, where copywriters copied ancient Greek and Latin texts Botanical and medical sciences were also preserved and monks dedicated themselves to the growing of herbs and the dtudy of herbal medicine in their cloistered gardens.

The Hortus simplicium (the Simple Vegetable Garden) was the garden where herbs and plants were grown (and are still grown today) that were used for their medicinal properties, and takes its name from the term medicamentum simplex, i.e. Medicinal herbs.

For centuries in the monasteries, in rooms called “officina” (from where the word “officinalis” for plants comes), these herbs were dried and preserved in special cupboards, before being used to make medicinal products: essential oils, syrups, teas, ointments and creams were obtained from the leaves, flowers, roots and bark steeped in alcohol or infused in water. Hospices and hospitals soon sprung up alongside the monasteries, where the sick, needy and pilgrims could find assistance and care.

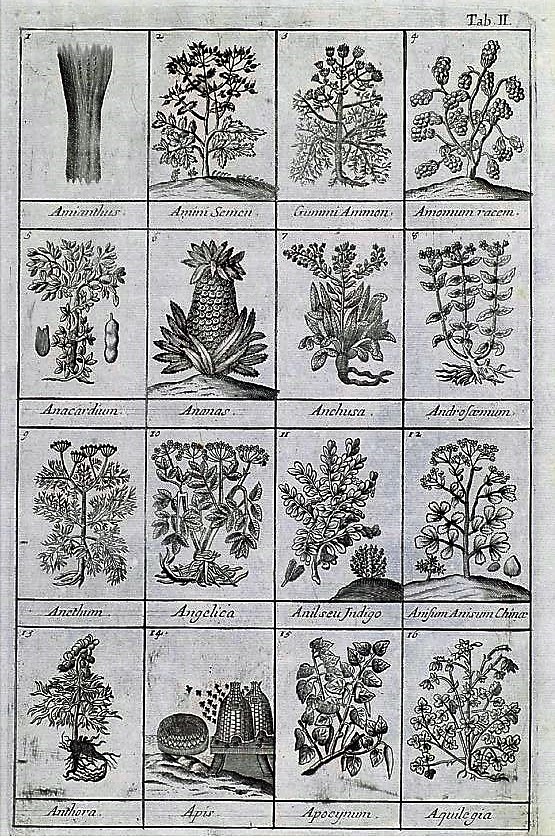

Precious studies and cataloguing of medicinal plants carried out by the monks allowed a rapid development of pharmaceutical science, also spread through depicted catalogues of all the herbs, called Hortuli, in which the characteristics and virtues of each plant were illustrated.

Bibliografia

- D. CONTIN, L. TONGIORGI TOMASI, Quando l'arte serviva a curare. Immagini botaniche dalla Bibliotheca Antiqua di Aboca, Aboca Edizioni 2015.

- R. FERRARA (a cura di), Immagini botaniche dalla raccolta del Fondo Rari della Biblioteca dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Istituto Superiore di Sanità 2010.

- LEONHART FUCHS, De Historia Stirpium, Wemding 1501 – Tubinga 1566.

- NICOLAS LEMERY, Dizionario overo Trattato universale delle droghe semplici. Edizione terza accresciuta, Venezia 1751.

- G. MANGANI, L. TONGIORGI TOMASI (a cura di) Gherardo Cibo. Dilettante di botanica e pittore di “paesi”. Arte, scienza e illustrazione botanica nel XVI secolo, Ancona 2013.

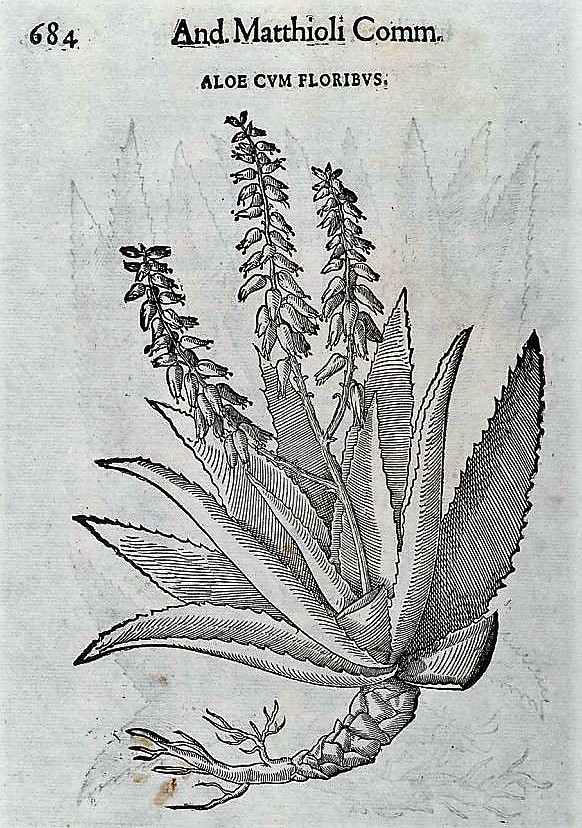

- PETRI ANDREAE MATTHIOLI, Commentarij secundo aucti, in libros sex Pedacij Dioscoridis Anazarbei de medica materia, Venetijs 1558.

- PETRI ANDREAE MATTHIOLI, Commentarii in sex libros Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei de medica materia, Venetiis 1565.

VR

VR