The garrison

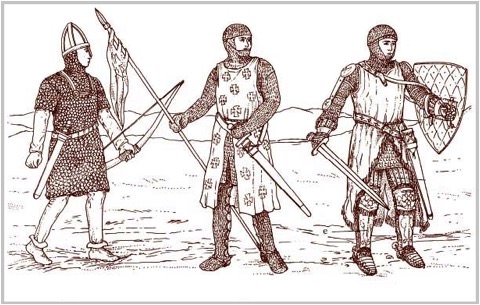

The castle’s defence was guaranteed by a contingent of armed men, called "garrison", which lived permanently in the fort (fig. 1).

Members of the garrison were not numerous and even in cases of actual war soldiers could be counted more often as dozens rather than hundreds. In addition to defending the castle and its occupants, the soldiers had to guarantee escort duty to merchants, especially in the areas most exposed to attacks by brigands.

Their presence inside the manor also implied the existence of spaces for their accommodation, stables and warehouses for weapons.

Horsemen in the twelfth century wore a long chain mail coat, a conical iron helmet and were protected by a long almond shaped shield; later, however, in the thirteenth and fourteenth century, over a jacket of padded cloth they wore an armour made of metal plates, while a camail safeguarded their head and neck and a helmet covered their head. They were armed with swords and lances.

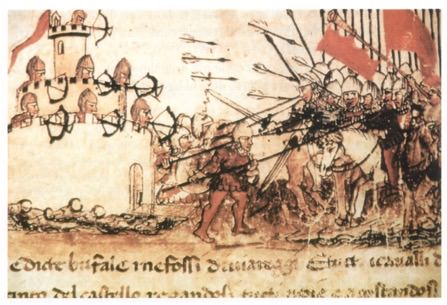

The defence of the castle also included the presence of archers with bows and crossbows, who hurled arrows and daggers at enemies from the top of the walls.

Sardinian castles once had a predominantly military role, but their technical defence mechanisms are still not clear today.

These fortresses were built near important crossroads which were essential for the passage of people and goods and, therefore, in places of great importance for the economic development of the surrounding area. However, the number of soldiers in these forts was very modest, as each of them held an average of 10 armed soldiers.

There was, therefore, a considerable discrepancy between the number of soldiers and the space to be defended, even if the knowledge of the territory and of the environment by those who fought, could explain the fullest use of significantly reduced contingents.

Were castles manned by such a small number of soldiers really a deterrent for a possible enemy attack? Not numerically, but no invasion can hope to have a lasting impact if garrisons from which counterattacks could originate are left behind, especially if they were joined by troops from other castles and fortresses which were part of a single defensive system.

The Middle Ages, in fact, also had means to communicate with allies guarding the other fortresses, through runners, fires, mirrors or pigeons, thereby agreeing the moves to be undertaken.

Bibliografia

- J. ARMANGUÈ I HERRERO, Uomini e guerre nella Sardegna medioevale, Cagliari 2007.

- G. FOIS, Appunti su alcune problematiche riguardanti i castelli in Sardegna e nel Giudicato d’Arborea, in V. GRIECO, I catalani e il castelliere sardo, Cagliari 2004, pp. 39-64.

- C. GRAVETT, I castelli medievali, Novara 1999.

VR

VR