Archaeological area of Mount Sirai

- Pre-nuraghic period - Late Ancient and Early Medieval Age, III millenium B.C. - VII century A.D.

Monte Sirai is the gateway to Sardinia’s history, an expression of the memory of places in the Sulcis region: to the south and west are the islands of Sant’Antioco and San Pietro; on the opposite side, the full view of the town of Carbonia and crossing towards the inland, towards wheat and metal (figs. 1-2).

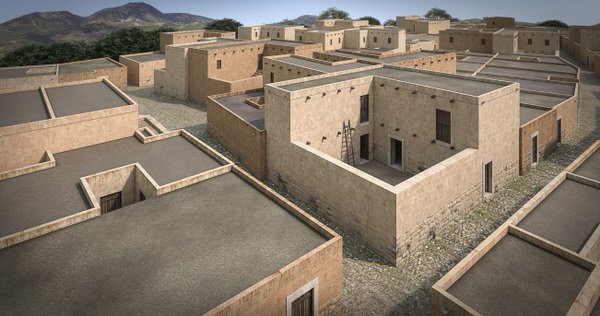

Monte Sirai, that was present in the prehistoric and Nuragic ages, contains a large amount of buildings along the high plains (fig. 3), a choice that was strategically aware of the landscape and intense use of the inhabitable surface area. A short distance from the acropolis and separate from it, there are the necropolis and the sacrificial area known as the ‘tophet’.

A fortified entrance precedes the settlement, arranged into blocks dedicated to private and public life: the former characterised by dwelling, crafts and production environments, the latter by small squares and urban and communication roads, and the temple. The religious space of the Astarte temple spread over the remains of a Nuragic site and was used for centuries. This monuments is one of the strongest symbolic evidence of the relations between the Phoenician and Nuragic populations, as can be seen in the archaeological materials found (figs. 4-5).

Several buildings have been investigated thoroughly, such as ‘Casa Fantar’ (fig. 6), ‘Casa Amadasi’, ‘Casa del lucernario di talco” (fig. 7), and others that are coming to light and use such as the ’Casa di tufo’: they are houses with solid, separate walls, stone bases and higher parts in stones or rough brick, also built with two floors. Spaces sometimes with internal courtyard.

The oldest parts of the settlement - preceded by Neolithic and Nuragic presences and with some Punic and Roman elements, the development of which outside the living area must still be defined - can be dated at the 8th century B.C. Red slip (red paint) pottery, typically Phoenician, native pots, sculptures, bronze figures and amulets, contemporary to the ones from the nearby Sant’Antioco, San Giorgio di Portoscusco and the Island of San Pietro, support this ancient beginnings. In the later 7th and 6th centuries B.C., intense building went on along the entire highland: the necropolis with incineration site, where the deceased were cremated and accompanied by classic trilobate-edged and mushroom shaped urns, precious ornamental and magic items and Greek pottery from Corinth all correspond to this phase of life.

The next phase, which began with the conquering of Sardinia by Carthage in the last decades of the 6th century B.C, continuing until the first half of the 4th century B.C. Cannot easily be seen in the buildings, due to the overlapping of various eras, but is well documented by the Punic pottery, Athens vases with black and red figures on them, commercial amphoras, terracotta figures and the Hypogeum necropolis from the same period.

Monte Sirai enjoyed its period of maximum expansion between the 4th and 2nd centuries B.C., between the late Punic age and the Roman Republic age, when the settlement took on the shape of a town, which is still visible and the tophet sanctuary was opened.

The necropolis are situated in three essential areas north of the acropolis, with an extraordinary chronological, typological and spatial sequence: from the Phoenician tombs (mostly in the ground, used with the ritual of cremation and with interment to a lesser extent) to the chambers of the Carthaginian age, from interesting architectural and decorative solutions (such as lithic masks or the symbol of the goddess Tinnit on one of the pillars in tomb no. 5 (fig. 8). These tombs were allocated to high social class family groups.

Other evidence points to burials in amphoras, cremation, tombs with double burial; the use of Phoenician cremation for infants in a later age, but which perhaps date back to the previous culture is also documented.

The cemeteries occupy an increasingly larger area, due to the demographic increase and the need for new spaces, showing the presence of different cultural traditions.

The presence of the tophet (fig. 9), a sacred area reserved for the burial of infant ashes in urns (a periodic ritual of sacrifice according to some experts; according to others, the place for premature deaths or miscarriages; the ceremony always foresaw a sacrifice of purification using fire), and is proof of the urban culture - as it is linked to it - and an increased population of the site, arranged at the edge of the dwelling area, as per tradition. The digs indicate a presence from a short time before the mid 4th and throughout the 2nd century B.C.

The burial area was made up of similar urns, containing the ashes of deceased children (about four hundred have been found) covered by plates and buried in the ground. A stele made from various types of stone and Egyptian and Greek style decorations, or simple patterns, were placed as visible signs. There was also a small temple with various functional area, that could be reached by a ramp and steps, in this area.

The settled area of Monte Sirai was abandoned for a long time in the early decades of the 1st century B.C. but was then inhabited again in the Late Ancient time, with extensive levelling of buildings between the 6th and 7th centuries A.D.

Bibliografia

- A. ASOLE, Le vicende dell’insediamento umano nella SardegnaSud-Occidentale (Sulcis) tra medioevo e età moderna, in V. SANTONI (a cura di), Carbonia e il Sulcis. Archeologia e territorio, Oristano 1995, pp. 419-438.

- V. ANGIUS, in G. Casalis, Dizionario geografico, storico, statistico, commerciale degli stati di Sua Maestà il Re di Sardegna, Torino 1833-1856.

- P. BARTOLONI, Monte Sirai, Sassari.

- P. BARTOLONI, I fenici e i cartaginesi in Sardegna, Sassari.

- M. GUIRGUIS, Monte Sirai 2005-2010. Bilanci e prospettive, in Vicino & Medio Oriente, 16, pp. 51-82.

- M. GUIRGUIS, Monte Sirai 1963-2013, mezzo secolo di indagini archeologiche, Sassari.

- M. GUIRGUIS, Monte Sirai 2014. Le nuove indagini nell’abitato e nella necropoli, in Quaderni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Cagliari e Oristano, 25, 2014, p. 441.

- M. GUIRGUIS, R. PLA ORQUIN, L’acropoli di Monte Sirai: notizie preliminari dallo scavo del 2010, in M.B. COCCO, A. GAVINI, A. IBBA (a cura di), L’ Africa Romana - Trasformazione dei paesaggi del potere nell’Africa settentrionale fino alla fine del mondo antico, Atti del XIX convegno di studio, Sassari, 16-19 dicembre 2010 , pp. 2863-2867.

- S. MOSCATI (a cura di), I Fenici (Palazzo Grassi, Venezia. Catalogo della Mostra) , Bompiani.

- P. XELLA, Per un ‘modello interpretativo’ del tofet: il tofet come necropoli infantile? in G. Bartoloni et alii, Tiro, Cartagine, Lixus: nuove acquisizioni (Atti del Convegno Internazionale in onore di Maria Giulia Amadasi Guzzo, Roma, 24-25 novembre 2008), Roma, pp. 259-278.

VR

VR