Archaeological area of Tharros

- Phoenician-Punic Age - Roman Age, IX century B.C. - VII century A.D.

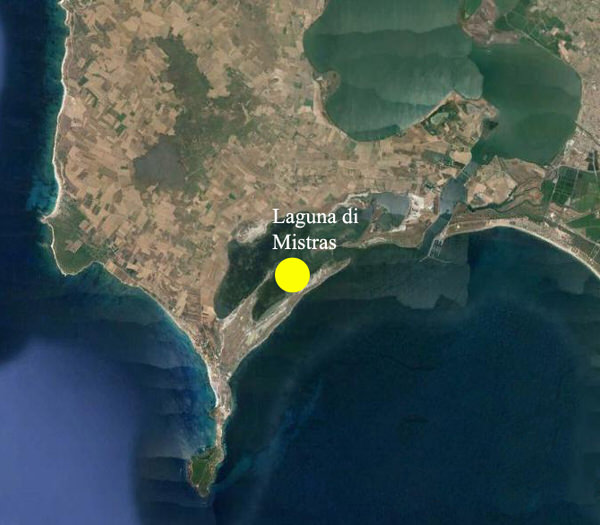

The city of Tharros is located on the Capo San Marco peninsula that, together with the opposite Capo Frasca point, are the extreme points of the wide Gulf of Oristano, locally known as the dead sea.

The urban centre stretches along the eastern coast of the peninsula, looking out onto the dead sea, standing on the slopes of Su Muru Mannu and on Torre di San Giovanni, that partly protect it from the strong Mistral winds (figs. 1-2).

The city ruins were only partly excavated therefore the reconstruction of the urban centre’s layout is lacking in some parts, especially for the older parts; these, in fact, are partly covered, partly destroyed by later constructions. Even the latest phase of the city, in the Byzantine Age, is not well documented due to the extremely modest nature of the structures that were not well preserved. What remains, however, is nought to restore the image of the city for us, or rather the images of the various cities that stood on the site over the centuries.

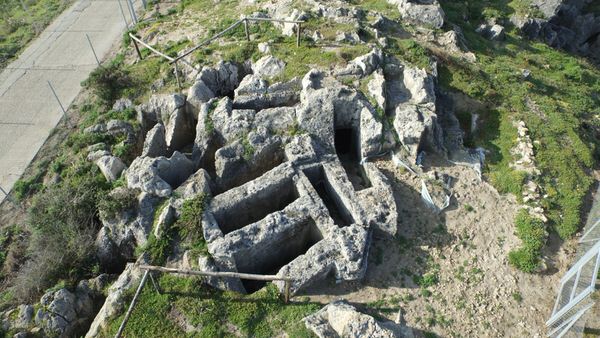

The Capo San Marco peninsula was lived in and frequented during the Nuragic age and there are still traces from the Middle Bronze Age, between 1600 and 1300 B.C., one of which is located in the highest part of the Su Muru Mannu hill, underneath the Phoenician-Punic tophet and that has been excavated. There are a small number of circular huts, detached and joined together around a courtyard, but it is not sure of whether there was a Nuraghe or not (figs. 3-4).

The materials found on site only allow us to date the initial stages of the Nuragic village, as the settlement of the later Punic tophet brought about the destruction of the final levels of living, but the several ceramic fragments found around the area can confirm that village life continued until at least the 8th century B.C.

The part of the area where Tharros stands was the centre of early contacts with the world outside the island, for a number of reasons. One of the main reasons is the direction of the winds and sea currents, that makes the return route from the Iberian peninsula eastwards touch the Balearic Islands and then the Gulf of Oristano exactly. Here the ships could find a sheltered mooring with a hinterland rich in resources and with a large population; a positive situation for trade and relations.

The main landing point, which then became a port, and only recently identified, was on the Mistras lagoon (fig. 5) just three kilometres north-east of Tharros.

The period in which Tharros was founded as a real urban centre has not yet been identified.

The presence of almost-oriental people, mostly Phoenician, is proven from the 8th century B.C. But frequency in the form of allocating new arrivals with the local communities, without the creation of new settlements, is apparently seen. Based on new research, especially in the southern and northern necropolises, and by reviewing old data, the Phoenician city of Tharros can be traced to the final decades of the 7th century B.C.

There is nothing left of this centre, destroyed and covered up by the massive urban work of later centuries, and the only evidence we can find is in the two necropolis centres, mainly the northern one, which has unfortunately mostly been devastated by the nineteenth century digs (figs. 6-7).

The presence of objects originating outside the island, including eastern, Etruscan and Greek items, inside and outside the tombs in the broadest sense, offers us a picture of an important centre.

An importance that increases considerably in the later Punic era, for which we have a good number of documents.

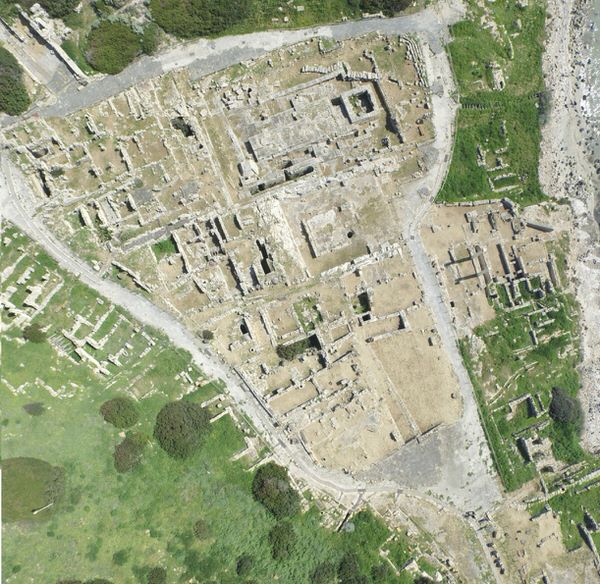

We must mention that the areas of the city investigated so far (even if not completely) in the digs are separated into two main sectors: A) the Su Muru Mannu hill and B) the base of the Su Muru Mannu and San Giovanni hills; areas of houses and public building outlined by Roman era roads stretch between these two hills, which are still to be brought to light (fig. 8).

If we start from the Su Muru Mannu hill, we meet the best-preserved fortress in Sardinia. The top of the site is in fact surrounded by a wall that is still preserved on the western and northern sides. The structure is an imposing one, built in large irregular blocks of basalt rock, dry built, and was already repaired and renovated in ancient times (fig. 9). There is a postern on the western side, where the intention of some kind of decoration can be seen, given the insertion of regular blocks in light sandstone (fig. 10) that was blocked up.

Blocked up about 50 B.C. There is another wall opposite this one, built with the same technique, that forms a long moat together with the previous one (fig. 11). Previously, this fortress was considered to be Punic, but more recent investigations bring us to believe that the current aspect is one due to renovations carried out in the Roman Republican Age in the 2nd century B.C.

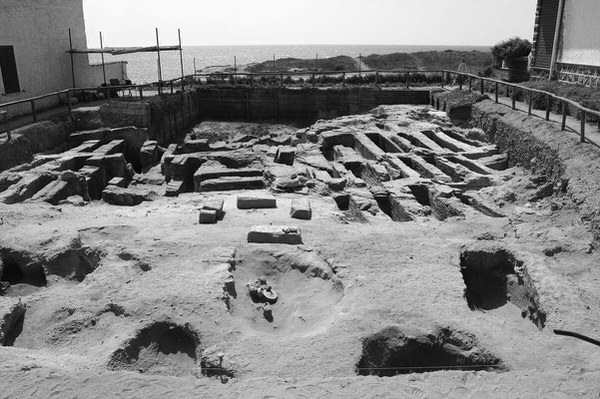

Once the reason for the existence of such a large construction had ceased to exist, the moat was placed out of use and partly filled in during the second half of the 1st century B.C. A small funeral chamber was built opposite the postern and the moat was filled by an Early Imperial Roman necropolis, mainly made up of beehive tombs (figs. 12-13).

The space behind the fortress wall, where the Nuragic village stood, was used during the Phoenician and Punic ages for the placement of tophets. This meant the placement of urns with cremated remains inside them (fig. 14) and the laying of sculpted stones, with no structural work. During the Roman Era, this area was used to build several constructions of an imprecise nature and many stones were used again to form the bases of such buildings (fig. 15).

Immediately south of the tophet, there is an empty area, which was once the entrance to the city from the city walls, now also recognised as a small amphitheatre that was originally surrounded by earthen terraces.

Roman ruins begin to appear clearly on the southern slopes of Su Muru Mannu. Two large roads, paved in basalt and with a central sewer that served the drains from the adjacent houses (fig. 16) divide the area into three large blocks. These have not yet been dug, but houses can be seen in the top part, and public buildings, including thermal baths (fig. 17) in the lower part.

The Roman Era roads, from the Imperial age, divide the city into well-defined areas, with a large triangle, containing public holy structures towards the sea and houses towards the hillside (fig. 18).

The northwestern tip of this triangle has a square occupied by a small building in the centre, most probably a holy aedicula which can no longer be seen, with the castellum aquae facing onto it. This was a large cistern that receive the water from the aqueduct, and with a public fountain placed on the front of it (figs. 19-20).

The triangular block also includes some holy buildings, including the semi-column temple from the Punic Era (fig. 21), named thus as its long sides are flanked with

Semi-columns sculpted with relief work in the base rock (fig. 22). The entire structure was covered up in the 2nd century A.D. and other constructions were built that no longer exist. There is an apparently empty space alongside the building described above, surrounded on three sides by natural cut rock, and open on the side facing the road, identified by the excavator Gennaro Pesce as the “Semitic style temple” due to its particular layout. The foundations and remains of the walls of two small holy buildings, with traces of mosaic floors, dated to around the 3rd century A.D., and surrounded by an unpaved corridor have been identified (figs. 23-24).

There are the remains of a similar temple structure on the opposite side of the road, built in the second half of the 1st century B.C. above a podium of large blocks that can be reconstructed as a temple with four columns on the front; the two columns that can now be seen are modern reconstructions (figs. 25-26).

We are at the heart of the urban centre of Roman Tharros, where most public buildings were found. On the seaward side, there is a large, badly preserved thermal baths buildings, named “thermal baths nr. 1”, just north of the temple next to the shore (fig. 27-28).

This building was renovated and changed over time, but at the time of the excavation the heated rooms could still easily be found, while the cold rooms had already been ruined (figs. 29-30).

In the late Roman era, the northern part of the thermal baths was incorporated into a Paleo-Christian basilica, of which the hexagonal baptismal font remains. (fig. 31).

The public area of the Roman city continues southwards, where there is another thermal building, in better condition, known as the Convento Vecchio thermal baths (fig. 32). The name may derive from a late use of the structures as a shelter for monks, the only trace of which is a Byzantine tomb found in the entrance and used as a dressing room (fig. 33).

The building is lacking part of its eastern sector, that has been eroded by the sea, but still has a good elevation and shows the map and the typical thermal bath route: dressing room, cold bath room, and a passageway for the heated areas (figs. 34-35).

This building was built a short time after 200 AD, a period in which the Roman cities in Sardinia experience a surge in new constructions. The San Giovanni hill stands above the Convento Vecchio thermal baths, which was involved in considerable building work in the later Punic and Roman age (figs. 36-37).

In the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C., a large staircase was built, little of which now remains, that led to a small temple with a portico, named temple K, with distinctive architectural cornices found at the foot of the slopes (figs. 38-39).

In the Imperial Roman Era, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., the structure was extensively redesigned. The portico was divided into room, the entrance was blocked off and materials from the first building were used in the renovation, including the remains of a Punic inscription.

The remaining area of Tharros is occupied by Roman and Late Roman era houses, on which the adaptation and organisation work carried out in ancient times, make it difficult to define them exactly (figs. 40-42).

The accurate division of the city into “quarters”, separated by paved roads that bear off from the main roads, can be seen, and these also have an efficient sewer system (fig. 43).

Due to the varying altitudes on this site (fig. 44), the houses also have a varying map (figs. 45-36) and most of them have a second floor or a gallery.

Water supplies were ensured by a rich system of cisterns that collected rainwater (fig. 47) and wells (fig. 48) that took water from the groundwater.

The long life of Tharros can be seen in the changes in use of houses. Some of them contain traces of the deterioration of the urban fabric from a city living area to an agricultural production environment (fig. 49) as seen in the millstones for milling cereals, a primary source of nutrition.

The Vandal age also brought about the renovation of the public quarter on the shores of the Gulf of Oristano, with the creation of a place of worship in the thermal baths nr. 2 area and probably a convent in the Convento Vecchio thermal baths area. In the Byzantine age, the city centre began its deterioration, which slowly led to the city’s death, although the port was still used in Medieval times, although the exact location is uncertain.

The area was still populated in Medieval times, as seen by the church of San Giovanni di Sinis, originally built in the 6-7th century A.D. (figs. 50-52), and was rebuilt in the 11th century. This building is built inland from Tharros, about 500 metres north of the fortifications on Su Muru Mannu and is the repeat of a type of similar religious settlements, such as the church of Sant’Efisio a Pula, near the town of Nora (fig. 53).

Although life had moved elsewhere, the area was exposed to raids by Saracen pirates and the King of Spain, Philip II, as part of the interventions to protect the island, ordered the San Giovanni Tower to be built, that still dominates the site now (fig. 54). We do not know its exact date of construction, but the tower can be found in documents from 1591.

Other evidence of the city of Tharros can be found in the Phoenician and Punic necropolises, that are north and south of the inhabited area. The oldest part seems to be the one in the north (figs. 55-56), located on the western shore of the headland, in the current site of San Giovanni di Sinis, were Punic coffer tombs and Phoenician incineration tombs (fig. 57).

The southern necropolis suffered more from the nineteenth century plundering and mostly comprises Punic era hypogeum tombs (5th-3rd century B.C.) with well access, often with narrow, high steps along one wall (figs. 58-60).

Bibliografia

- E. ACQUARO, Tharros tra Fenicia e Cartagine, in Atti del II Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici, Roma 1991, pp. 537-558

- E. ACQUARO, C. FINZI, Tharros, Sassari 1986

- S. ANGIOLILLO, Mosaici antichi in Italia. Sardinia, Roma 1981.

- P.BARTOLONI, Fenici e Cartaginesi nel golfo di Oristano, in Atti del V Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici, Palermo 2005, pp. 939-950.

- P. BERNARDINI ET ALII, Tharros: indagini nell’area dell’anfiteatro romano, in The Journal of Fasti on line (www.fastionline.org/docs/FOLDER-it-2014-313.pdf)

- R. CORONEO, San Giovanni di Sinis, in V. FISHER (ed.), Chiese cruciformi bizantine della Sardegna, Cagliari 1999, pp. 37-39

- C. DEL VAIS, Per un recupero della necropoli meridionale di Tharros: alcune note sugli scavi ottocenteschi, in E. ACQUARO ET ALII (edd.), La necropoli meridionale di Tharros – Tharrica I, Bologna 2006, pp. 8-41

- C. DEL VAIS, Nuove ricerche nella necropoli settentrionale di Tharros (campagne 2010-2011): l’Area A, in ArcheoArte, 2, 2013, pp. 333-334

- C. DEL VAIS, A.C. FARISELLI, Nuovi scavi nella necropoli settentrionale di Tharros (loc. S. Giovanni di Sinis, Cabras – OR), in ArcheoArte, 1, 2010, pp. 305-306

- C. DEL VAIS, A.C. FARISELLI, La necropoli settentrionale di Tharros: nuovi scavi e prospettive di ricerca (campagna 2009), in ArcheoArte, supplemento al n. 1, Cagliari 2012, pp. 261-283.

- C. DEL VAIS, P. MATTAZZI, A. MEZZOLANI, Tharros XXI-XXII. Saggio di scavo nei quadrati B2.7-8, C2.7-8: la cisterna ad ovest del cardo, in Rivista di Studi Fenici XXIII (supplemento), 1995, pp. 133-152

- C. DEL VAIS ET ALII, Tharros: saggio di scavo sul cardo maximus, in OCNUS. Quaderni della Scuola di Specializzazione in Archeologia, III, 1995, pp. 193-201

- C. DEL VAIS ET ALII, Ricerche geo-archeologiche nella penisola del Sinis (OR): aspetti e modificazioni del paesaggio tra preistoria e storia, in Atti del II Simposio “Il monitoraggio costiero mediterraneo: problematiche e tecniche di misura”, Firenze 2008, pp. 403-414

- ENCICLOPEDIA DELL’ARTE ANTICA CLASSICA E ORIENTALE, s.v. Tharros (1966)

- ENCICLOPEDIA DELL’ARTE ANTICA CLASSICA E ORIENTALE (SUPPLEMENTO), s.v. Tharros (1997)

- A.M. GIUNTELLA, Materiali per la forma urbis di Tharros tardo-romana e altomedievale, in P.G. SPANU (ed.), Materiali per una topografia urbana. Status quaestionis e nuove acquisizioni, Oristano 1995, pp. 117-144

- M. MARANO, L’abitato punico romano di Tharros (Cabras-OR): i dati di archivio, in A.C. FARISELLI (ed.), Da Tharros a Bitia. Nuove prospettive della ricerca archeologica, Bologna 2013, pp. 75-94.

- A. MEZZOLANI, L’approvvigionamento idrico a Tharros: note preliminari, in E. ACQUARO ET ALII (edd.), Progetto Tharros, Roma 1997, pp. 122-130

- G. PESCE, Tharros, Cagliari 1966

- V. SANTONI, Tharros XI – Il villaggio nuragico di Su Muru Mannu, in Rivista di Studi Fenici, XIII, 1985, pp. 33-140

- P.G. SPANU, La Sardegna bizantina tra VI e VII secolo, Oristano 1998, pp. 78-96

- P.G. SPANU, R. ZUCCA, Da Tarrai polis al portus santi Marci: storia e archeologia di una città portuale dall’antichità al Medioevo, in A. MASTINO ET ALII (edd.), Tharros Felix 4, Roma 2011, pp. 15-103.

- A. TARAMELLI, Edizione Archeologica della Carta d’Italia al 100.000. Foglio 216, Capo San Marco, Firenze 1929

- C. TRONCHETTI, Tharros – Lo scavo della postierla e dell’edificio funerario nel fossato – Anno 1981, in Tharros XXIV – Rivista di Studi Fenici XXV (supplemento), 1997, pp. 39-42.

- E. USAI, R. ZUCCA, Nota sulle necropoli di Tharros, in Annali della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia, XLII, 1986, pp. 3-27

- R. ZUCCA, Tharros, Oristano 1984

- R. ZUCCA, Testimonianze letterarie ed epigrafiche su Tharros, in Nuovo Bullettino Archeologico Sardo, I, 1984, pp. 163-177

- R. ZUCCA, La necropoli fenicia di San Giovanni di Sinis, in Riti funerari e di olocausto nella Sardegna fenicia e punica (= Quaderni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Cagliari e Oristano 6/1989, supplemento), pp. 89-107.

VR

VR