Castle of Monreale

- Middle Ages, XIII-XV century A.D.

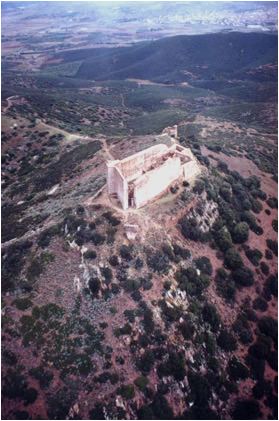

The castle of Monreale (fig. 1) was built during the second half of the thirteenth century on top of a hill 387 metres high, in the Municipality of Sardara (Southern Sardinia).

This high position (fig. 2) allowed easily controlling not only the surrounding plain (Campidano), but also the sa bia turresa, that is the main road that in the Middle Ages connected the city of Cagliari with Turris Libisonis (the current Porto Torres), joining the South to the North of the island.

As occurred in many medieval castles, the complex of Monreale (fig. 3) also included the castle itself (the keep) and the fortified village (the village).

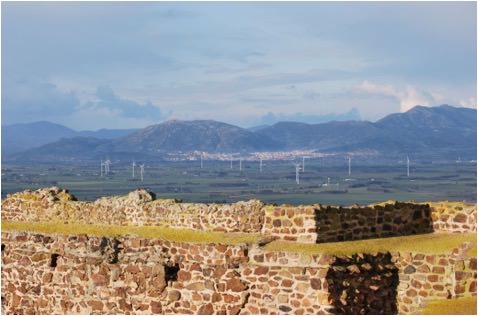

Currently, the remains of the walls are still visible on the ground: almost one kilometre long and with walls over two metres thick, they surrounded the houses built in a small valley between two hills, marking an irregularly shaped pentagon on the ground.

In order to better protect this settlement, the wall perimeter was reinforced at regular intervals by at least eight (possibly nine) towers, some semi-circular (fig. 4), others with a quadrangular plan. The keep is located on top of the highest hill at the southern vertex of the pentagon.

At least two gates allowed access to the fortified complex, one to the North towards the town of Sardis and the baths of Santa Maria is Aquas, and one to the West. Outside the north gate there are the remains of a small church dedicated to San Michele, to which a cemetery was annexed.

The two entrances to the village were joined by a road, still visible in the middle of the nineteenth century, known as sa ruga manna (the main road), set in a valley of the hill.

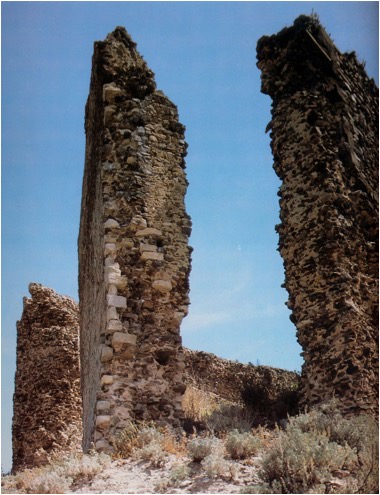

Only the robust outer walls and the walls of the rooms on the ground floor remain of the castle itself, unearthed by archaeologists who investigated this area over the last twenty years.

The keep, which has the shape of an irregular stretched trapezium, with the north and south sides parallel to each other and the Western one oblique in respect of the first two (figs. 5-6), encloses an inner surface of about 720 square metres.

Its west side, which looks straight out onto the bia turresa, has a particularly robust masonry, whilst the opposite side, to the east, has a quadrangular room with an elongated edge set against it.

The entrance (fig. 7) is set in the corner where the south and west perimeter walls join and the vertical grooves which allowed the gate to slide down as well as the rings that circled the cornerstones of the wooden doors are still visible (fig. 8).

This access (fig. 9) allowed reaching, through a corridor with some steps, a first courtyard paved with stone slabs, where the water intake of a cistern and an L-shaped bench leaning against the North and West walls are still visible.

From here one passed into the central courtyard, which was, in turn, arranged over three levels and around which all the inner rooms opened, placed in a gradually increasing size in order to follow the contours of the hill.

The various parts of the yard were connected by steps built with small stones bonded with mortar (fig. 10).

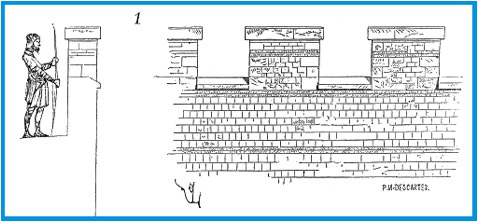

The high-rising elements are still standing up to around ten metres and they refer to areas spanning two floors, which lean against the perimeter walls of the keep; on top of these, where there are still traces of battlements (fig. 11), there were the walkways paved with earthenware (fig. 12).

The presence of the upper floors is proved by the presence, on the perimeter walls, of numerous square holes which had the purpose of housing the large beams that held up the wooden planks with which the floors were made (fig. 13).

For security reasons there were no openings on the outside walls, so all the spaces, both on the ground floor and on the upper floors, were only illuminated by windows overlooking the inner courtyard.

Thanks to archaeological research, it has been possible to understand the internal structure of the keep.

The ground floor was divided into five rooms on the north side, called by scholars alpha, kappa, iota, theta, delta; two on the south, one on the southeast (epsilon) and an area on the northeast side which has been interpreted as a tower (gamma).

The water supply was guaranteed by rainwater collected from the roof of the building through terracotta gutter pipes, which was conveyed into the two tanks in the various sectors of the courtyard, equipped with control systems and connected one to the other.

Food reserves, mainly consisting of cereals, were kept in silos in ground cavities and also in storage facilities in high-rising elements.

The entire fortification system of the complex consisted of an irregular building made of local schist, trachyte, granite and limestone stones, all bound by abundant mortar (fig. 14).

Bibliografia

- G. SERRELI, La frontiera meridionale del Regno giudicale d’Arborea: un’area strategica di fondamentale importanza per la storia medievale sarda, in Rivista dell'Istituto di Storia dell'Europa Mediterranea, 4, 2010, pp. 213-219.

- F.R. STASOLLA, Per un’archeologia dei castelli in Sardegna: il castrum di Monreale a Sardara (VS), in Temporis Signa, V, 2010, pp. 39-54.

- F. CARRADA, Il castello di Monreale: bilancio di un decennio di studi e attività, in Roccas. Aspetti del sistema di fortificazione in Sardegna, Oristano 2003, pp. 121-144.

- P.G. SPANU, Il castello di Monreale, in Archeologia a Sardara. Da Sant'Anastasia a Monreale, Quaderni Didattici della Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici per le Province di Cagliari e Oristano, 11, 2003, pp. 53-64.

- E.E. VIOLLET LE DUC, Encyclopédie Médiévale, tome I, Tours 2002.

- G. CAVALLO, Il castello di Monreale, in Milites. Castelli e battaglie nella Sardegna tardo-medievale, Cagliari 1996, pp. 28-30.

- F. FOIS, Castelli della Sardegna medioevale, Cinisello Balsamo 1992, p. 158.

- V. ANGIUS, s.v. Sardara, in Dizionario geografico, storico, statistico, commerciale dagli Stati di S. M. il Re di Sardegna, Torino 1853, vol. XVIII, pp. 893-907.

VR

VR